Summary

Part 2 in a series on gender and the Bible. (1 Corinthians 11:2-16) Nate and Tim discuss the first of six key New Testament passages pertaining to gender that have traditionally been used to support male authority. What is Paul really getting at about women covering their heads? Does “the head of the woman is man” really mean men are supposed to be in charge? Who gets authority over women’s bodies? And what in the world do angels have to do with any of this? All this and more as Nate and Tim take a closer look and show how most of us were taught that Paul was saying the exact opposite of what he really meant.

Transcription

Tim: Hey, welcome back to Almost Heretical. Last episode we started a series on Jesus, gender, authority, all that good stuff. And we’re going to continue that series this episode, getting into one of the first of the key passages we’re going to look at. But before we do, just want to remind you all, we would love to hear from you. Our email is contact@almostheretical.com. Any stories, questions, thoughts, even if you just want to vent some anger our way, we’d love to hear where everybody’s at and create some dialogue around this topic. So hit us up.

Nate: Okay, so Tim what are we talking about this week?

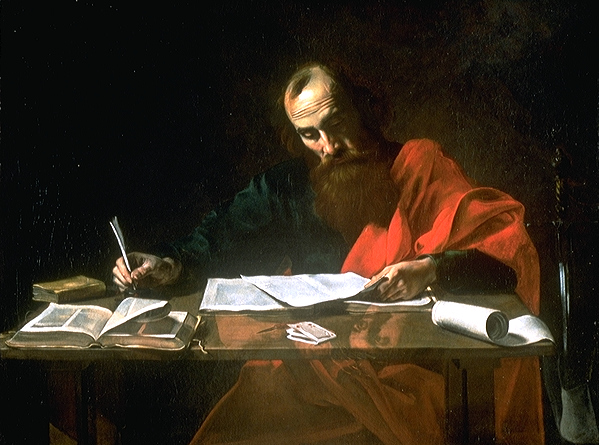

Tim: 1 Corinthians 11:2-16. Veils, heads, glory, angels, disgrace. All sorts of weird stuff.

Nate: Ah, okay. I always heard head covering, not veil. But okay I’ll read this, where are we going? Say it again?

Tim: 1 Corinthians 11:2-16.

Nate: 1 Corinthians 11… Okay. 2-16? Oh man, this is like, I remember when they would call on you to read a certain passage and you’re just hoping that it’s going to be two or three verses, and then you’re like, “Oh crap, it’s fourteen verses.” Whatever. Okay, buckle up! And then you do the thing where you’re like, scanning ahead making sure you can pronounce all the names.

Tim: [laughing] “Oh, I got Zebulon!”

Nate: [laughing] We’ve all been there. Okay, here we go. This is the NIV.

2 I praise you for remembering me—

Nate: The other one is when you kind of like, you read the first couple words and then you start looking around at people to make sure you’re in the right book. So tell me if I’m not reading from the right place. These are all my insecurities coming out.

I praise you for remembering me— in everything and for holding to the traditions just as I passed them on you. But I want you to realize that the head of every man is Christ, and the head of the woman is man, and the head of Christ is God. Every man who prays or prophesies with his head covered dishonors his head. But every woman who prays or prophesies with her head uncovered dishonors her head—it is the same as having her head shaved. For if a woman does not cover her head, she might as well have her hair cut off; but if it is a disgrace for a woman to have her hair cut off or her head shaved, then she should cover her head. A man ought not to cover his head, since he is the image and glory of God; but woman is the glory of man. For man did not come from woman, but woman from man; neither was man created for woman, but woman for man. It is for this reason that a woman ought to have authority over her own head, because of the angels.

Nate: Oh yeah, that verse.

11 Nevertheless, in the Lord woman is not independent of man, nor is man independent of woman. For as woman came from man, so also man is born of woman. But everything comes from God. Judge for yourselves: Is it proper for a woman to pray to God with her head uncovered? Does not the very nature of things teach that if a man has long hair, it is a disgrace to him, but that if a woman has long hair, it is her glory? For long hair is given to her as a covering. If anyone wants to be contentious about this, we have no other practice—nor do the churches of God.

Nate: Okay, that was it.

Tim: Okay, let’s just start with your gut reaction, probably been a little while since you read this passage, Nate. What’s some of the stuff that you immediately think of or things that you, ideas that you were taught or interpretations you’d heard?

Nate: Yeah, I mean it was kind of this whole hierarchy thing again, that God is at the top, and then man and then woman. But these aren’t roles of lording over or something like that, it’s supposed to all be in humility or whatever. But this is kind of the order of you know, authority/decision-making. And I’ve heard a lot of jokes over the years in Bible college and as a pastor, that kind of stuff of like, the husband making the final decision and needed to kind of control his wife. You know, but it’s often just in a joke but not in the way it actually happens in the family or whatever. Yeah, so just basically this is Paul doing what Paul does, which is talking about the hierarchy of God – man – woman. But then I knew a lot of people that wanted to take Paul at his word and not try to explain away the covering your head. And so I have some friends who go to churches where they cover their head. Which I always was like, hey, might as well follow all the things he’s saying and not just try to get out of one of them. So I was like, that’s kind of cool. And then I just noticed this one, I’ve obviously read it before, but as we’re on this topic. Verse 12 where he says, “For as woman came from man, so also man is born of woman.” I thought that was kind of interesting. You don’t have men without women. A little bit of the leveling of playing field there a bit. And for a while what I’ve sort of thought about this is, it’s very culturally bound to their world they were in, and that’s sort of how I make sense of what he’s saying here. It kind of sounds pretty bad for Paul. In my just plain reading, it sounds pretty bad for Paul, like it pretty well supports the complementarian worldview, I guess.

Tim: Yeah, I totally remember even in the stage of life where I was pretty strong leaning towards egalitarian, universal equality ideas, the best I could make sense of this for a long time was that the culture expected women to sort of know their place. And one of the ways they were expected to do that was to cover their heads, and Paul was basically giving in to the culture. He was, that part of him hadn’t really been shaped by Christ yet, and so the best way to make sense of this in any sort of decent, to create any decent theology of this was basically just to ignore that part, right? But what I’ve realized since is that that was actually making a similar error to what I think complementarians do in this passage, which is, again, breaking a pretty fundamental hermeneutical rule. Which is again, when there’s fuzzy interpretation or when interpretation is difficult and contested within a passage, then priority should always be given to interpretations that make for a thoroughly cohesive reading of the entire passage and the entire letter. In other words, if one interpretation is able to explain how all of the thoughts connect and how this presents one logical strain of ideas—

Nate: Wait, like the angel verse!

Tim: Exactly. One of my favorite verses or partial lines in the Bible. Just, “Because of the angels.” Which we’ll talk about in a sec. But basically, if there is the possibility of an interpretation that has a lot of explanatory power for the rest of the passage and the rest of the text, then that interpretation should always be given priority in the debate. And I’m thoroughly convinced that the complementarian interpretation of this passage, which we’ll get into, basically that this is Paul asserting that men by nature are authority figures over women and that Paul here is applying that idea by making women veil their heads, wear veils or head coverings, that that basically makes no sense in the context of this passage or this letter. And there are some other interpretations that actually make a lot of explanatory sense.

Nate: Okay, so let’s do it. So what is he actually trying to say then, if he’s not saying that. And then how does the, “For the angels,” or whatever. “Calling all angels,” or—what is it?

Tim: [laughing] That was a song, right? And then there’s Touched by an Angel? Actually, Touched by an Angel has far more to do with this passage than Calling All Angels.

Nate: I never watched—was that a show? Touched by an Angel? I never watched it.

Tim: Oh, yeah I kinda grew up on that.

Nate: Calling All Angels is a good song by Train, though.

Tim: You were at church. I was pretty much just watching Touched by an Angel.

Nate: [laughing] No, I never saw it.

Tim: Okay, there’s so much here. We don’t have space to cover all of it. There’s so much interesting stuff, it’s fascinating, and some of it’s really important. Okay, the first one, if any of you guys follow the debate, the debate in scholarship for some time now has been over the meaning, intended meaning of the word head. It’s a metaphor. It can mean both authority and source. Those are the two most common meanings in Paul’s usage and in biblical usage of the metaphor. Oftentimes it kind of insinuates both. So the complementarian side wants to say, “Hey this word here, when Paul says I want to you realize that the head of every man is Christ, the head of every woman is man, the head of Christ is God, that that means authority. So just switch out head with authority.” And on the egalitarian side, people push back to say, “No, no, no, it means source.” That the source of every man is Christ, the source of the woman is the man, and the source of Christ is God. And essentially, the primary push back against that idea of source is people basically asking the question, in what meaningful way can man be the source of woman? And because they don’t know the answer to that question, they’ve basically said, “We’ve stumped you, and this clearly is a matter of authority.” But Westfall does some really good careful, detailed work here. But basically in both this passage and in another passage which we’ll look at in another episode, where Paul’s using the same head metaphor, there’s evidence within the passage multiple levels of evidence that what he means is source. So for instance, look at verse 12. “For as woman came from man, so also man is born of woman. But everything comes from God.” It’s part of the same argument, right? We’re all here in the same passage. And it’s referencing back to the same idea. And there are two things going on here. The first is just basic Old Testament careful theology. So Paul grew up on the Torah. He read the Pentateuch and the rest of the Old Testament writings through and through and through, had them memorized. And what’s the story? Basically you have a Genesis 1 creation account and a Genesis 2 creation account. How are human beings created, according to those two stories?

Nate: The rib of the man.

Tim: Right. In one account, you just have this statement that, “God made mankind in His image. In the image of God He created them. Male and female He created them.” Just a statement. Then in the second account you have Adam and Eve. It’s almost these two different depictions. And in that account, God creates Adam, adam, man from the dust, and then takes the side. “Rib,” is a bad translation; it basically means, “from the side of him.”

Nate: I don’t know if anyone ever taught me this, but I grew up thinking that I had one less rib on one of my sides because of that whole thing that happened. So I remember feeling and thinking that I felt the difference. I know that’s crazy now. I don’t think anyone ever taught me that, I’m not putting anyone on blast here, but I think I just interpreted it that way.

Tim: You’ve told me that before, and I am equally astonished every time I hear it.

Nate: That’s another way of saying he thinks I’m stupid.

Tim: [laughing] No! Just, wow, the world is weird and Christians are weird. All that.

Nate: You’re welcome.

Tim: So the idea there is, “side.” The whole point is it’s this narrative depiction of the equality; they’re equal essence. And even complementarians will grant that there’s equal essence in creation. But what’s interesting is, just think, you basically have one story that just says men and women are created and they’re equally the image of God. They’re both corulers with God is the implication. Then another story where man is created first and then woman is created from the man. That actually sets up some really interesting theological reflection that Paul and many other careful Jewish readers would have been able to do in deducing some significance from those two different stories and the way they overlap together. But that’s the first sense that, in verse 12, “Woman came from man.” Eve came from Adam. That’s the idea: he was the source of her life. He was the source of, literally, her body, her existence. And that’s been taken to mean that therefore that somehow gives Adam supremacy, but that’s nowhere in this text. It’s just saying he was the source. Then Paul actually reciprocates it, “So also man is born of woman.” So actually what Paul sees here is that you both have this story back in Genesis 2 that Adam was the source of woman. And he is comparing that to Christ being the source of man, or kind of the life-giving first fruits, the one who pioneered, went ahead, and provided access to life, and now can give life to man. And compares that to Christ as—you know, it’s kind of that begotten language—who came from or was sourced from God. But he can reciprocate that at the same time and point out that also, by the way, men come from women. Women have the babies. Man is born of woman. And he’s basically using this in the opposite. It’s not to say that men are therefore higher status, superior to women, supposed to be in charge. He’s actually pointing out that it’s reciprocal. The source language actually goes both directions. He says, “But everything comes from God.” So I remember, you and I have probably both seen them. There are these pictures with a pyramid, and it’s like God – Men – Women. I don’t know if they put children beneath that or something.

Nate: I’ve seen them as an umbrella, not a pyramid. It’s like this umbrella, which I think comes from this verse.

Tim: Yeah, this and another. So big picture, the first big piece is Paul’s clearly, he’s signalling this multiple times throughout this passage and the other passage where head is used as a metaphor, he’s signalling that he’s thinking about the Genesis accounts. He’s thinking about the creation accounts. And there’s another piece of Jewish creation ideas or theology that plays in here, which is the idea that part of woman, basically in the Adam and Eve story, part of woman’s being created as a matching, fitting, wonderful partner to the man, was when God created Adam, Adam was created in the image of God. Now pairing that with Genesis 1, you know that you can’t say that means woman wasn’t created in the image of God, because it says, “Male and female they were created.” But there’s this sense, and this is attested to in Jewish literature, that because the woman was then created from the image of God, she was the image of God and the image of Adam, who was also the image of God, in the sense that she was doubly the image of God. And this was actually a thing of honor. Basically the reference here that she came from Adam is actually giving her higher status; it’s not pointing to her inferiority. But related to that was that there was this prominent idea that a woman’s beauty, physical beauty, was integral to what it meant for a woman to be a glory of man. So when you look down at verse 7, “A man ought not to cover his head since he is the image and glory of God.” Here image and glory are kind of used synonymously. “But woman is the glory of man, for man did not come from woman, but woman from man. Neither was man created for woman, but woman for man.” The idea is that this narrative depiction of a woman being created that is suitable for man, or that man came to desire, was basically this high literary depiction of male attraction towards females, and it basically was hinting at sexuality and beauty and the prominent role of feminine beauty in relationships in the world, and suggesting that a woman’s beauty is a significant part of what is true about women. That women and women’s bodies are aesthetically pleasing to men by design, and that is something Paul is celebrating. Not denigrating. It’s not a threat. Female sexuality is not a threat to men in Paul’s thinking. It’s a gift from God to men that Paul’s highlighting here. Now why am I bringing this up? It’s because this makes cohesive sense of Paul’s head in different languages and his uses of hair, and we’ll see in a second, it makes sense of the, “angels,” line. So I think you and I may have talked about this at some point, Nate, but did you know there’s actually prominent scholarship out there that has discovered or rediscovered that in Hippocrates—who is one of the early Greek medical thinkers, medical philosophers, basically doctors—where we get the Hippocratic oath in medical practice?

Nate: Ah, right.

Tim: That in his writings, he was the leading medical expert of his day, that women’s hair was deemed essentially a counterpart to male genitalia.

Nate: Huh. Yeah, I don’t know what to do with that. I feel like there’s a joke here, and I’m supposed to—I feel like that’s my role, is to do the joke here, and I—yeah, I don’t know what joke to do. I’ll edit it in!

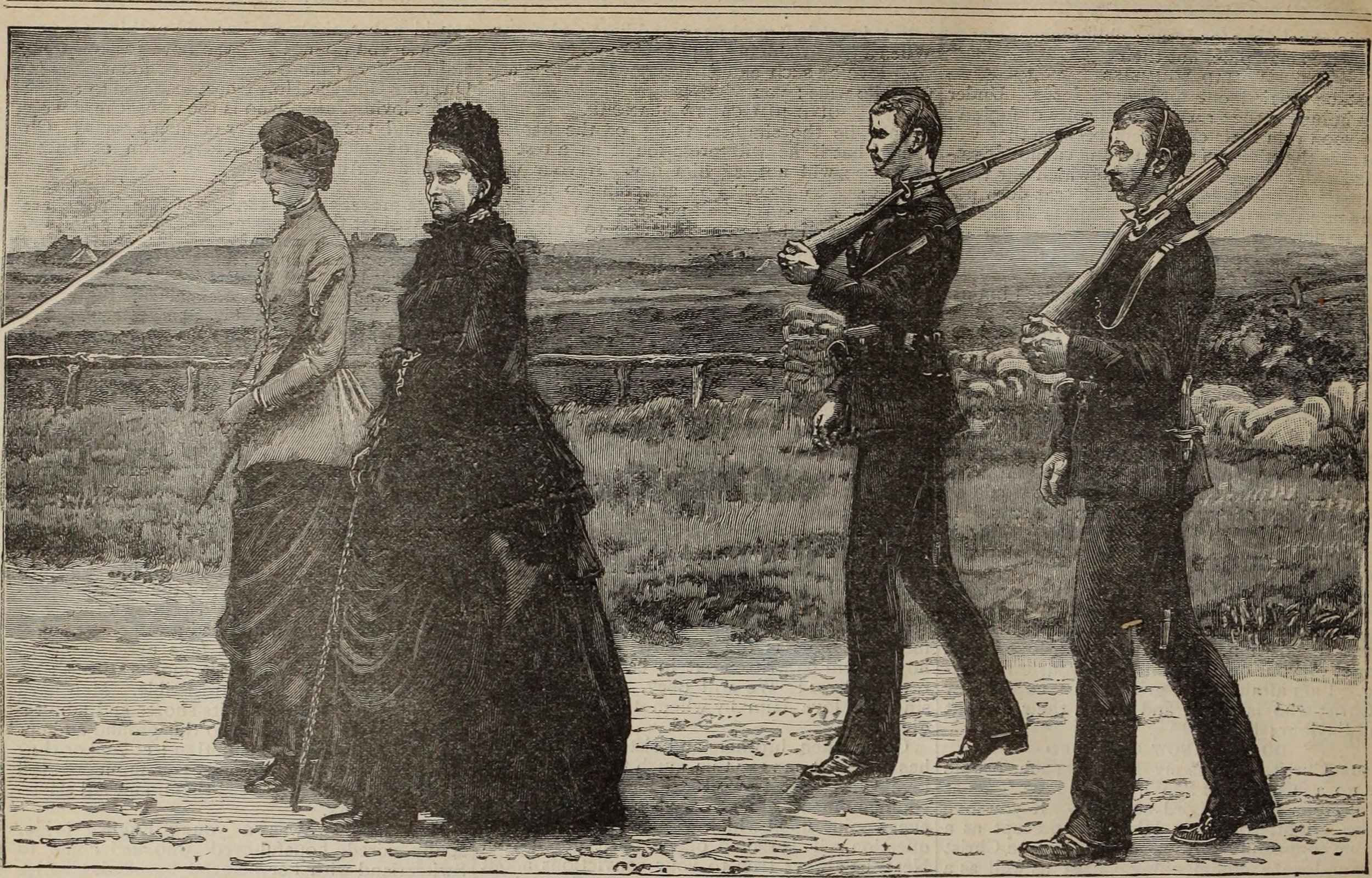

Tim: [laughing] Alright, if you come up with one, you can hit me. So it’s debated over how much Paul agrees with that idea or not, but what’s clear is that Paul is in somewhat similar position of the leading science of his day, in the sense that women’s hair was highly associated with female sexuality and fertility. So on one end of the extreme, Paul literally thinks that female hair is their genitals and is responsible for reproduction. On the other end of the spectrum, he just thinks hair is a symbol for beauty, sexuality, fertility, reproduction for women, and that it is not considered that culturally for men. That doesn’t mean Paul is teaching this. This is just the world that he is speaking into. So connect all these pieces. There’s this idea that it’s basically touching on, in this interpretation at least, the idea of head is focusing on this idea not of authority but of source, which relates to the conversation because it’s talking about sexuality, and there’s this long-standing idea that woman came from man as a literary way of speaking about positive feminine sexuality. Which is exactly what hair represents in the Greco-Roman culture of Paul’s day. Okay so from there Paul talks about how for a man, it’s actually considered dishonoring and disgraceful to cover his head, but for a woman it would be considered disgraceful, even to the point of the humiliation of having your head shaved, for her to not cover her head. Now this is just basic fact of Greco-Roman scholarship: it was explicitly illegal in the Roman empire for prostitutes and female slaves to wear a veil. And this just a piece where Westfall and so many others, most of them women, have done so much important work on veiling in cultures that veil, on what it means to women that veil. It’s pretty foreign to western culture. I learned a lot, and a lot of it actually is coming from equivalence in modern day veiling cultures like in the Middle East that are actually far more similar to Greco-Roman context than our own western culture. So we’ve interpreted this as, the assumption is women didn’t want to veil. They were wanting to be rebellious, and Paul lays down the law by referencing male authority, lays down the law that they have to stop being rebellious and cover their heads. And there’s a much better, much more explanatory case to be made read in context that what was likely happening was that women in the church, which these are house churches meeting in someone’s living room, that at least one or more of the women wanted to veil their heads, but were being told they shouldn’t veil their heads by men in that church. Now why would that have happened? And again, this where I’ve—

Nate: They want to see that hair!

Tim: Well, it’s complicated, but the reason prostitutes and female slaves were not allowed to veil is what a veil meant, what it symbolized and communicated was that that woman was off of the market sexually and therefore was a woman of honor. So if you were a middle to upper class free woman, you could wear a veil when you went out to the market that basically told the men in society, “You are not allowed to rape me.”

Nate: That sounds like a terrible place!

Tim: Honestly, such a gnarly world. And I don’t think America’s great, but so many eras in the world were so harsh for women. So the reason why slaves—basically prostitutes and female slaves, there’s a blurred line between the two because they were sexual property of male society—the reason they were forbidden from wearing veils was because they were not free women sexually. They were sexual property, and therefore could legally be sexually assaulted, but a woman who was the wife of a man was protected. Not on the basis of her equality, that she was worthy of protection; she was protected on the basis that she was a man’s property, and therefore she could not be sexually assaulted because that would be performing an offense against her husband.

Nate: Okay. Yeah, okay, so what’s Paul saying here, then?

Tim: So picture this, in this church, it is in all likelihood that there were both prostitutes and female slaves in this church community that Paul is writing to in Corinth. Actually women were by far the most predominant disciples in the church, some of the most predominant leaders in the early church, and actually there has been a lot of scholarship that’s focused on how women were most likely by far the most effective evangelists, spreading Christianity throughout the Roman empire. And Christianity was most popular amongst the lower classes, precisely because of the anti-hierarchical ethic that we were talking about in the last episode. So you can picture a scene where you have this community where Paul has said elsewhere that there is no longer any social status differentiation. The differences between Jew/Gentile, slave/free, male/female have been nullified in this community.

Nate: Ahh, I see.

Tim: And for the first time ever.

Nate: Wait, wait, wait. Can I do it? Can I do it?

Tim: Oh, sure.

Nate: So now because he’s leveling the playing field as he’s always done, Paul’s always doing that, he’s saying every woman cover their head. He’s not saying whether covering the head is the right thing to do or the wrong thing to do. He’s not saying that. He’s saying there’s not going to be two groups of women where one of them doesn’t have their heads covered—the prostitutes—and one group does—the honorable women. He’s like, “Everyone’s just going to cover them. You guys are all honorable in the sight of this community and of God.”

Tim: He’s doing that and more. So he’s breaking the law—

Nate: Oooh!

Tim: By telling low status women that they can veil and recover their dignity and honor within this community. He’s also telling men, every man in the house church, that they do not have authority to decide what women should do with their body. So look at verse 10, this is one of the most blatant mistranslations in the history of the church. If you read the NIV, they do a pretty good job. They say, “It is for this reason that a woman ought to have authority over her own head.” We’ll skip the, “because of angels,” part for a second. The whole point of Paul’s giving this decree is to say that women in the church get to have authority over their own damn head. Okay? Look at what the ESV did. We’ve already pointed out, ESV was explicitly set out to make a complementarian version of the Bible. It says, “That is why a wife ought to have a symbol of authority on her head.” There’s literally no word symbol there. The word is just authority, power. It’s the same word, and the ESV and a few other translations literally just can’t comprehend this, that Paul would grant women authority over their own bodies, so they just insert two words that aren’t in the text. The point of the passage is explicitly here. Paul is empowering women in the community, using his power. We’ve talked about this in past episodes. This is a good example of when people have power and therefore have a responsibility to use it on behalf of others. Paul does that sometimes; sometimes he lays down his power. Here he uses it to tell men, “You do not have authority over the women in this community like the society tells you you do.” So legally, socially, they are granted authority over all of the women in that community, especially the slaves and prostitutes. And Paul says, “No, no. You don’t have authority. Women get authority over their own body.” And this is supported—we don’t need to get into the details of all this—by this idea, “Because of the angels.” It shows that what’s going on in Paul’s head here is the idea of sexual risk. It’s showing that in context here, a veil represented protection from sexual risk. To put a veil on meant that you were no longer legally allowed to be raped. It seems to me this line, “Because of the angels,” the only logical reference is back to that weird stuff we talked about a while back in Genesis 6.

Nate: I was wondering if you were going to get back to that, yeah.

Tim: Yeah.

Nate: Because that’s like episodes 2-7 or something like that? You should check it out!

Tim: Somewhere around there. Early stuff, yeah.

Tim: It’s one of the only sensible ideas. Back in Genesis 6, you have one of the chapters of the story of what’s gone wrong with the world is that women are not only unsafe sexually, relationally, socially with men, but also in Genesis 6 they get raped by these angelic beings. And the point is to depict how cruel the world has become for women. That’s one of the primary ideas of these Genesis 1-11 stories about the fall is that the world has become a sick place for women. That’s not how it was designed to be. Those with power, men and even angels, use that power to take advantage of women. So Paul seems to be hinting at that. And there’s possibilities that there was kind of this overarching that when the church worshipped, that they were joining in the heavenly host in worship, so there was some sort of cosmic contact happening between Christians and angels. But regardless, it seems that the reference is to the risk presented by angels, which seems to affirm that the idea here is largely about women’s hair as a sexual object and sexual symbol in the society that he is explicitly writing to the church, both to the men and the women in the church, to say, “Hey, who gets to decide what women do with their body, their sexuality? It’s the women, not the men.” In other words, it’s the exact opposite of how this has been interpreted, that Paul is writing to tell the women what to do and tell the men that it’s their job to tell the women what to do.

Nate: Ooh, I like this. I like this! And this is just number one! This is just the first passage we’ve gone over. You say there’s even better ones that we’re going to hit, and that’s what we’re going to do on this show. That’s what we’re doing in this series. That’s the end of this one. Come back next time for the next episode in this series. If you have questions, comments, concerns or push back or frustrations with us or with the system and the way every thing is, you can email us at contact@almostheretical.com. We read every single email and we pretty much respond to every email, too. So alright, we’ll talk to you next time.

Tim: Peace.

Nate: Ooh, I’m liking this, I’m so excited, Timmy!