Summary

Part 8 of the gender series. Nate and Tim discuss Paul’s words to Timothy concerning “elders” and “deacons”. Can women be elders? Or is Paul mandating male leadership? Is he even creating formal “church offices” at all? And what do these titles even mean? We seek to answer these questions and more while showing how and why we usually get Paul so wrong. Passage: 1 Timothy 3

Listen to our short episode responding to the Social Justice Statement.

Transcribed

Tim: I used to love Nas. That song One Mic was like my jam for a while.

Nate: [laughing] Are you actually going to play this? No, okay, okay. Welcome back to Almost Heretical! We are in a series that we are getting very close to wrapping up. [laughing] Tim, turn that off!

[One Mic by Nas playing]

Tim: C’mon, do you remember this?

Nate: [laughing] This is what we’re spending our precious internet connection on?! That you have like, one kilobyte a second and you’re spending it on—

Tim: No, I can download all day, man. I just can’t bootleg stuff to the internet.

Nate: Oh yeah, you’ve got the incredibly slow upload speeds. Okay, anyways! Welcome back to Almost Heretical. We are in the midst, near the end, of a series on gender and Paul and the Bible, and it’s been so much fun to do. And it’s been our most listened to thing we’ve ever done, which is I think telling, because I think people are ready for a change here. That’s what this tells me, and just with the questions and everything that we receive on this just tells me that people are ready for a change and it’s more than time for that. Today we want to announce something, and if you’ve been to our website, you have seen this, almostheretical.com. We are trying something. Something we hear back a lot from people is, this is awesome but it’d be really fun to talk to people face-to-face, in real life! They want to have these conversations with other people where they can talk to them and get to know people who are also rethinking and processing through lots of different issues for lots of different reasons. I mean, everyone’s at a different place for different reasons based on their experiences or things didn’t work anymore for them, or whatever it is, and we want to have these conversations in real life, face to face. And so we didn’t really know how to do this, and so we just decided, “Let’s just pick a date.” So we just picked a date that seemed like it was good, and in Portland because I’m already in Portland, and Tim’s pretty close to Portland, and it’s pretty easy to get here for people. So anyways, we decided November 11th and 12th we are going to have a series of conversations in Portland. And really what this means—well, Tim you explain.

Tim: Yeah, I mean, I’ve noticed in some of my favorite podcasts, especially in the space of people rethinking Christianity and faith, that there seems to come this inevitable point where the topics and conversations create a kind of cohesiveness, a kind of sense of, “These are my people, we’re like-minded, I don’t feel as alone as I used to just knowing there are one or two people out there that feel the same way.” But that reaches its limit sometimes in terms of what listening to a podcast or even online engagement can accomplish. So literally the only goal for this is the same goal for why we do the show but on a smaller, more intimate scale. It’s just to help people feel less alone, specifically by getting together, meeting each other face to face, and connecting. So once you sign up, when it gets closer to the date, we’re going to send out a survey and essentially just ask what is it everybody’s most passionate about or interested in discussing. So we’re not teaching, there won’t be a conference center, we’re not renting out any spaces.

Nate: There’s no band!

Tim: We’re not charging anybody money, there’s none of that stuff.

Nate: There’s no debrief fireside chat at the end with the host. No, it’s not that.

Tim: So literally, I think about five people are signed up now. If it gets to be more than fifteen, honestly, I don’t know how we’ll do it, so we’re assuming it’ll just be a small group of people. And we’re just going to pick different places, bars, breweries, restaurants, cafes, basically from Saturday morning through Sunday evening, and pick a few different time and say, “Hey, this slot, people wanted to talk about this idea or these few ideas.” And we’re just going to get around and talk. No one person’s going to have a microphone. It’ll just be a free space to share our stories, share where we come from, pains, experiences, wisdom we’ve gained along the way, all that. And so basically, if any of the kinds of topics we’ve talked about on the show, whether it’s gender, , patriarchy, , American history and how that’s affected the church and theories of atonement, any of the stuff we’ve covered. One person’s really excited to talk about hell because they feel like they’re a heretic at their church and they can’t talk about their feelings at church so they want to come meet some people in Portland and talk about that. Anything like that, if you feel a strong desire, strong enough to warrant you making your way to Portland for a weekend, basically the point is just to get together and talk.

Nate: Yeah, and all the details, all that kind of stuff, we can help you figure that out as far as airport pickup, where to stay, all that kind of stuff. There’s lots of stuff to see here, too, so make a weekend out of it and let’s have these conversations together. We’re pretty excited about doing that. Okay, so that was the first announcement, and you can find out more at almostheretical.com, just click the banner at the top about Portland and all the information is there, and then email us if you have any questions or anything like that. Okay, so there’s going to be this new thing we want to try to do at the end of episodes, which is a question segment. And we get a number of questions that come into the show. Some people leave them in audio form, sometimes through email, sometimes on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, all the different channels. We get these questions, and I wanted to have this place where we can bring those all together at the end of a show after we talk about whatever on the show and just kind of do quick hitter questions. But a lot of times with the nature of the topics that we’re dealing with, the questions warrant more than just a two or three minute answer. And that’s the case with the question that we’re going to do today. But before we get to that, I just want to say, if you have any questions, we’re not saying we’re giving the answer on this. It’s more our response, our thoughts, and how we’ve processed through this and how we’ve heard other people process through these things. I just mean, when you ask us a question in general, it’s not like the final answer on that topic. But if you do want to do that, you can go to almostheretical.com/ask, and you can either record a question there or email in your question and we’ll try to answer that on the air at some point. It might be in the future at some point, if it’s a question that we want to do a whole episode on, but if it’s something we can do a quicker response to, we’ll try to include that in the new question segment at the end that we’re going to hopefully get to here soon. But today’s question is one that we already wanted to do an episode on in this gender series and it’s one that it seems like we’ve heard from a number of people. So we got this question from Kevin Reed on Facebook, and I’ll just read it. Kevin says, “Loving the gender series. I’m about halfway through reading Westfall’s book, which is amazing. A few things. One, does Paul think women can be elders and deacons if it’s clear in 1 Timothy 3 that elders and deacons must be husbands? Westfall doesn’t seem to tackle this question based on my brief perusal through the index.” And then the second. Should I do the second question now, or should we answer that one and then come back to it?

Tim: Oh, just do the whole thing.

Nate: Okay. “In the case that Paul didn’t think women could be elders or deacons, basically taking the stance that Paul was wrong in terms of church offices of elder and deacon that they can only be men. Some people take this line of thinking with the issue of homosexuality, saying that Paul would not have affirmed homosexual lifestyle, but that Paul was wrong.” And then Kevin says, “Would love to hear your responses on the podcast.” We’re doing a whole episode.

Tim: This one goes out to you, Kev.

Nate: And here we go.

[One Mic by Nas playing (again)]

Tim: [laughing] It’s such a good song! Okay, yeah here we go. So there’s a reason we built up to 1 Timothy 2 when we walked through the first set of episodes on different passages related to gender, is that one’s really the central point from which people basically develop gender hierarchy in the church and in the home, and even outside in the culture. But 1 Timothy 3 is another sort of pillar in that this is where the hierarchy of church ministry roles, particularly the role of elder, and we’ll see how deacon and pastors get sort of lumped into that as well. 1 Timothy 3 is where that is totally grounded, which has been long before complementarianism was ever invented, the church went toward an all-male model of leadership. So that’s been around Catholic church, Eastern church, forever. So I think Kevin’s totally right in asking the question. Do we need to look at this as, “This is what Paul taught”? Or is it possible to look at this as basically we’ve confused what Paul was saying and misinterpreted it? And his side comment is something we’ll get into significantly in future episodes on other topics on things like homosexuality, which is basically discussing that argument about whether Paul would feel differently today than he did two thousand years ago. But our whole premise in this series has just been to look at major mainline predominant scholarship. These are not obscure, cultic, left field ideas, but real scholars producing reliable trustworthy work to say that you don’t even have to make that argument, that Paul was actually intending to say things throughout that mean and meant to him the exact opposite of what we’ve said that they mean. And so we’re actually going to look at 1 Timothy 3, and then we’ll pull in Titus 1, it’s a bit of a parallel. And I’m going to make the same case here that what it sounds like Paul is doing, restricting the role of elder and basically church leadership to men, is exactly not what Paul is doing. So we won’t even talk about that argument of, “Should we just say Paul’s wrong? Would Paul change his mind?” Instead we’re going to walk through a case of saying Paul never said what we think he said in the first place.

Nate: Okay, let’s do that. Um, do you want me to read this?

Tim: Yes.

Nate: Right from the beginning? 1 Timothy 3:1?

Tim: Yep, through 12, and then we’ll read a little in Titus, too. I’ll do the Titus one, I’ll let you do 1 Timothy 3.

Nate: Okay.

Tim: But yeah, 1-12.

1 Here is a trustworthy saying: Whoever aspires to be an overseer desires a noble task. Now the overseer is to be above reproach, faithful to his wife, temperate, self-controlled, respectable, hospitable, able to teach, not given to drunkenness, not violent but gentle, not quarrelsome, not a lover of money. He must manage his own family well and see that his children obey him, and he must do so in a manner worthy of full respect. (If anyone does not know how to manage his own family, how can he take care of God’s church?) He must not be a recent convert, or he may become conceited and fall under the same judgment as the devil. He must also have a good reputation with outsiders, so that he will not fall into disgrace and into the devil’s trap. In the same way, deacons are to be worthy of respect, sincere, not indulging in much , and not pursuing dishonest gain. They must keep hold of the deep truths of the faith with a clear conscience. They must first be tested; and then if there is nothing against them, let them serve as deacons. In the same way, the women are to be worthy of respect, not malicious talkers but temperate and trustworthy in everything. A deacon must be faithful to his wife and must manage his children and his household well.

Tim: Titus 1:5-9

5 The reason I left you in Crete was that you might put in order what was left unfinished and appoint elders in every town, as I directed you. An elder must be blameless, faithful to his wife, a man whose children believe and are not open to the charge of being wild and disobedient. Since an overseer manages God household, he must be blameless—not overbearing, not quick-tempered, not given to drunkenness, not violent, not pursuing dishonest gain. Rather, he must be hospitable, one who loves what is good, who is self-controlled, upright, holy and disciplined. He must hold firmly to the trustworthy message as it has been taught, so that he can encourage others by sound doctrine and refute those who oppose it.

Nate: Here comes the devil’s advocate: Tim, it says he all over the place, first of all. And then it says he has to have a wife, he has to manage his household well, and manage his wife. It’s talking about a guy here in both these passages.

Tim: [laughing/groaning] Nate, I so hate when you play devil’s advocate. It makes me mad.

Nate: It makes me mad, too. I don’t like when I do that, either.

Tim: [laughing] Yeah, I mean it’s worth repeating that while I think the complementarian interpretation of the New Testament is completely without merit, logical scholarly merit, and is toxic and hurtful to people, that I also understand why millions of us read these passages—for instance, you and I both just read from the NIV in our English translations—and feel like that’s the only thing that it could be saying.

Nate: Yeah, because I know people that want to think differently than this and they just can’t because the Bible doesn’t say that, and so they’re so hung up on that, rightfully or wrongfully so, whatever, that they can’t think that. You know what I mean?

Tim: Yep. I understand. So I appreciate someone who’s actually willing to ask the question, if that’s where they’re coming from, should we just admit that Paul was wrong? Or should we discuss the fact that, maybe not using the language of right or wrong, should we discuss the fact that these ideas are hurtful and we know them to be hurtful, and should we consider changing them even if this seems to be what Paul wrote? And we’ll get into that. Some of that stuff, especially like, what are the epistles, and how do we think of these letters as scripture anyway? But again, in this series, we’re just going to… What if Paul wasn’t saying what it sounds like he’s saying, and actually what if our English translations are part of why it makes it sounds like that’s all he possibly could be saying? So we’ll mostly talk about 1 Timothy 3, but obviously you can see the comparisons in Titus. He’s speaking to some sort of function or role or type of person called elder and gives pretty similar ethical injunctions, right, that he be a faithful spouse. But it’s assumed, at least it’s using the masculine term of husband, and that’s the basis for why the church has said that leaders must be men.

Nate: Do we even know where the whole idea of an elder came from? Obviously Jesus wasn’t talking about that? And so Paul just kind of like, starts talking about it. Do we have any idea where that was borrowed from, or why that even came to be? Or is that a really long answer?

Tim: Uh, it is a really long answer, but that’s what most of today’s show is going to be on, actually.

Nate: Oh, good! Let’s do an episode on this! Right now!

Tim: [laughing] Yeah. Okay, so good question. First I’ll just point out, so we’re going to do a second episode outside of the gender series sometime in the future, could be more, it’s something I’ve been fired up about for a while, but basically asking the question, was Paul creating offices at all? Was he creating church structure? The language you hear thrown around all the time is this is how God orchestrated the church, or this is how God wanted the church to be organized, or this was God’s ordained, designed plan for the church. Is any of that true at all? Or is Paul doing something completely different from that here? And my answer to that question is going to be, I actually think almost all of the logic, the interpretation that points to the New Testament and sees this as basically blueprints for how to organize the church is completely off basis and is part of why we’ve misconstrued Paul’s theology of power and his theology of gender so badly. But we’ll fill out some of those details later. First, just want to point out, basically: there are a lot of terms that Paul uses in different places, and the reason some of them get muddled together, like elder and this word that the NIV translates as overseer, is because it seems like here in Titus, verse 6 says, “An elder must be blameless, faithful to his wife,” and then verse 7 says, “Since an overseer manages God’s household.” So it seems those get lumped together. And that happens some other places where it seems like the boundaries between these different functions are bleeding out. So I’ll just say that about Titus and then we’ll go to 1 Timothy 3. Okay, here’s what I’m going to start with, Nate. Is I’m going to lay out four interpretations that I’ve heard of 1 Timothy 3, and I want you to think for a sec and point out problems you see with each interpretation as we go through.

Nate: Alright, let’s do it.

Tim: You’re going to play angel’s advocate.

Nate: [laughing]

[transitional music]

Tim: Okay, let me back up a sec. If you didn’t notice, just see that in 1 Timothy 3:1-12, you can almost split it in half. Paul addresses overseers up top, which I just said basically is paired with elders in Titus; and then deacons in the second half. Okay? That’s how the NIV translates it. Notice that the injunctions to both are almost identical. So verse 2, “Now the overseer is to be above reproach, faithful to his wife, temperate, self-controlled, respectable, hospitable, able to teach,” the list goes on. Now verse 12, “A deacon must be faithful to his wife and must manage his children and his household well.” You basically have similar injunctions but that same, almost verbatim line of being a faithful husband of one wife who manages his children and his household well.

Nate: Or even verse 8 with the deacons, “In the same way, deacons are to be worthy of respect.”

Tim: Exactly.

Nate: He said worthy of respect there and then above reproach, it’s kind of the same thing.

Tim: Totally. The way it lays out in most Bible translations I’ve seen, it’s very obscure. Like, the ordering is different in the different injunctions, the part about being a good dad and a good husband is at the bottom with deacons, but it’s at the top with overseers, so it becomes hard to see the parallel. But what you gotta see is whatever Paul is saying to elders about being a husband or a family man or whatever he’s saying, he’s saying to these deacons as well. So because of that, that’s why I say there are four possible interpretations. I would say only one of the four is possible. So here we go. The first one is that Paul is creating offices—that’s the language we usually hear—creating offices of elders and deacons requiring that both can only be men. What’s the problem with that?

Nate: Well, I mean the main one that jumps out is that it’d be easier to say that then the way he did say that. And if you’re giving the—so that’s my main problem. But the second problem would be, in my head, if you said essentially the same things for both of the two groups, overseer and then deacon, then why are they two different offices if you’re saying the same things for them? He didn’t say, “For the overseer you need to do this, this and this; for the deacon you need to do this, this and this.” Um, yeah. Did I find the right problems?

Tim: Uh, no, I think some of that’s good. There are some differences in the lists. So what a lot of complementarians will point out is that basically whatever is in the elder list and isn’t in the deacon list, which includes teaching, that’s what elders are supposed to do. So that’s actually how a lot of churches go through deciding what the biblical role of elders is, which then gets extrapolated oftentimes as to what the biblical role of what men can do that women can’t do. Sidebar that, but basically they go through the list and they pick out the few things that are different. So there are a few things that are included in the elder list that aren’t in the bottom list. But the biggest problem in my mind is in Romans 16. And we’ll talk about this either this week or next week. Romans 16 is historically one of the biggest problems in all of the Bible for complementarians because Paul left and right is honoring and naming various women in various different high status roles within the church society. So the first verse of Romans 16 says, “I commend to you our sister Phoebe, a deacon of the church in Cenchreae.” So how can the same Paul, if his meaning here in 1 Timothy is that, “Hey, there’s this job, deacon, and it has to be a married man that does it,” how can he then in Romans 16 exalt a woman, Phoebe, as a deacon?

Nate: Right. Yeah, that’s a problem.

Tim: So acknowledging that problem and admitting it, churches get a little creative. And this is actually the church world that I came from, this is what we did, and it’s this to say that Paul is establishing offices here, but women are only prohibited from being elders and not deacons. And then usually, historically, pastors has been lumped in with elders. Some churches then try to separate them so you could have women pastors but not women elders. My church was in the middle of having a over that. But still, elders was never even on the table, so they basically siloed off and said, “Okay, in the bottom half of this, Paul’s talking to deacons, top half Paul’s talking to elders, but Phoebe’s a deacon, therefore women can be some sort of deacon role,” and then every church makes up what that is. Like small group leaders or Bible study teachers, or Sunday school teachers, whatever. You define deacon up to your own. What’s the problem with this?

Nate: Well, just on the last part there, you’re defining what the role is anyways, because those things aren’t necessarily talked about here. But then also, if for both overseer and deacon he says man and he says husband of one wife, manages his household well, all that kind of stuff, then how does that work if another place he says there was a deacon that was a woman? Could that also negate the whole male thing for the overseer role as well?

Tim: Totally.

Nate: Plus, there’s other places where Paul, we’ve talked about this on other episodes, where Paul talks about women prophesying, which as we’ve kind of defined, there’s really no difference between that and teaching. So that kind of feels like a problem here, too.

Tim: Totally. Yeah, I mean I actually think once you see it, you realize it’s one of the most obvious glaring cases of selective literalism in all protestant New Testament theology.

Nate: That was a really big statement.

Tim: Yeah, I mean think about it, you literally have one, not even a whole chapter, twelve verses, and you take half of them and you say, “Paul meant literally that only men can do this.” And then you take the other half you’re like, “Eh, Paul didn’t mean that so literally.” It’s literally just picking and choosing.

Nate: So you’d be happier with someone interpreting thing this way, to say women also can’t be deacons.

Tim: Yes, but that’s where I… okay so, because that would be more consistent, right?

Nate: It’s consistent but still missing what Paul’s trying to say.

Tim: But then I go, okay, well even that is selective literalism because Paul isn’t anywhere saying, “Whoever aspires to be an overseer must be a man.” It says, “Now the overseer is to be above reproach, faithful to his wife.” And then goes on to talk about managing his own family well and seeing that his own children obey him, or being a good caretaker of his children. Paul’s drawing the analogy of, if you’re going to take care of people in the church, you better be a good parent, right?

Nate: Right.

Tim: So if you’re going to take this literally as Paul describing God’s ordained plan for organizing the church, you would have to logically and consistently apply what actually one of my seminary professors did. And that is to say that Paul here is making a rule that all deacons and all elders must be married men with children.

Nate: Yeah, I know, it seems like very few do that, go to that level. And if you’re not going to go to that level, then you’re really not listening to what this passage is saying. You’re not taking it literally, right?

Tim: Totally, yeah. I have a lot of issues with that interpretation, which we’ll get to in a sec, but I can at least give it the respect of saying it’s consistent. It’s not completely, obviously nitpicking pieces that fit certain systems and then ignoring other pieces. It’s making the interpretive decision that Paul’s laying rules and then it’s treating this literally and saying, “Okay, we’ve got to listen to those rules.” Basically, there are a lot of ways you could pick at that. There are a lot of reasons to be offended by that kind of thinking in today’s day and age. But here’s the logic that at least my seminary professor, who espoused this idea, backed it up with. Basically he sees that being married, and I think he would say, he thought this was Paul speaking to men only, but he would say for men and women, being married and having children builds a lot of character, helps you learn how to love people, helps build patience, discipline, those sorts of things. And so Paul must have been seeing that kind of character development as a kind of prerequisite for these ministry functions in the church. Which, I mean, I can at least get the sense of that. That at least makes some sort of cohesive explanatory sense, right?

Nate: Yeah. And I think maybe there’s some aspect of that, like it takes a little bit of, you gotta get knocked down in order to, and you know, have gone through hardships in order to help other people go through hardships. Just a general, we look for that in leaders in general in the world.

Tim: Yeah. So I want to say, if you want to take 1 Timothy 3 as Paul passing down instructions, a manual basically, for setting up church leadership and church offices, then that’s the way you have to apply it. But here’s why that is completely inconsistent. In 1 Corinthians 7, Paul spends almost an entire chapter making the exact opposite argument from what that seminary professor I had said. And that is, he thinks it’s better for Christians to be single and unmarried specifically because if you’re a person with a family, the concerns of being a family person get in the way of the kinds of Christian ministry, gospel-teaching, proclamation, being out there, being an apostle like Paul, that you could be doing. So he specifically says, “These are not things that serve as prerequisites, being a good family person doesn’t serve as a prerequisite for you doing ministry, it’s an obstacle that I wish you wouldn’t have in your life. It’s better for you to be single.”

Nate: Hmm, that’s right. Yeah, I forgot about that.

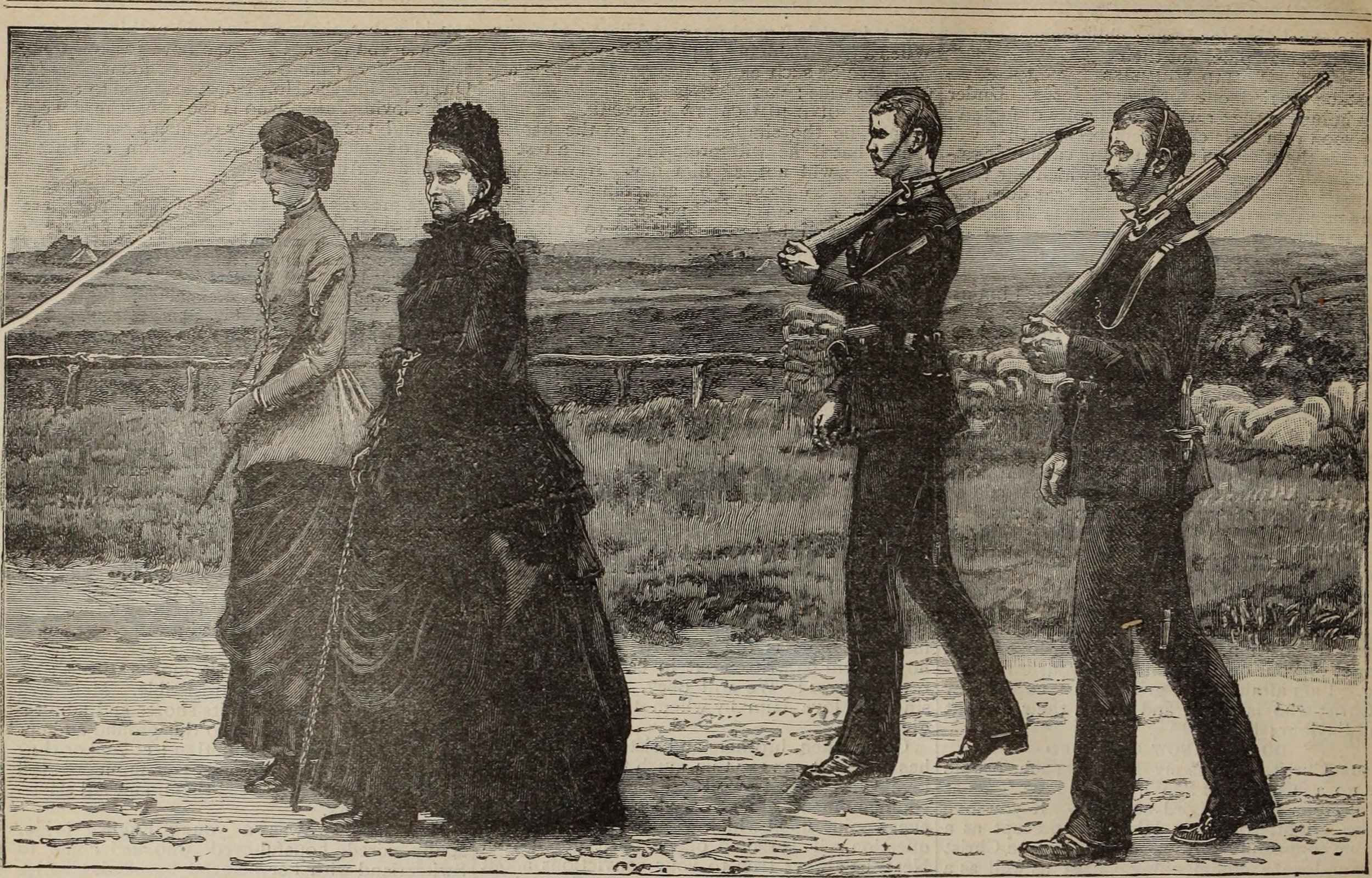

Tim: So the idea that here Paul’s laying down this universal code that it’s better to be married to be in leadership goes completely fundamentally in opposition to Paul saying in 1 Corinthians 7 that it’s typically better for people to be single if they’re the kind of people who are gifted with singleness. So that throws a whole wrench I would say in all three of these interpretations, which to me points to there only being, honestly, one legitimate reasonable interpretation. Which is that Paul here is not creating church offices. This is not Paul the apostle giving us God’s ordained plan for church hierarchy at all, but that actually what Paul is doing is he is acknowledging roles and functions within the Christian communities that already existed because they existed in the culture and would have existed whether Paul was ever there or not. And then he speaks to people who are in those positions, people who have a little bit of authority in the community, and applies Christian ethics to those people. And we’ll that there are actually parallels between the ethics that Paul applies in terms of being a respected person within the community, someone who hasn’t ruined the community’s good reputation with outsiders, someone who’s able to teach the ways of the community and the faith of the community to others, and who’s essentially a respected older family figure, a patriarch. That those expectations, actually people, sociologists, have discovered that those were some of the typical expectations of what tribal societies look for in their own elders who have nothing to do with Christianity. And so for the rest of the episode I’m going to make the case that what Paul is doing is he is acknowledging that there are these roles of elders in a community who serve this kind of function or task of a caretaker, overseer, within that community, who are there regardless of Paul’s work. Regardless of this letter of 1 Timothy, there are going to be people in these roles. And then Paul is therefore giving them ethics to live by. And the reason he’s assuming that these roles will be men is because in a patriarchal culture like the Greco-Roman world, but more specifically like the Jewish world, which these Christian communities were a sect of, only men would have been given that sort of patriarchal tribal elder function. And so Paul looks at those men and says, “If you’re in a position with that kind of power, I’m going to lay a whole bunch of Christian ethics on you to make sure you don’t that power. So rather than him saying, “These are the roles and men have to be the one to fill these roles,” he’s saying, “These men are going to be in these positions, and men in those positions have to obey these ethics.” So by the time we get to the end I’ll try to make the case that in today’s day, when we look around in a much more feminist and egalitarian culture that thinks women can be just as much the head of a household or the head of a company as men, that Paul would have, similar to Kevin’s question, can we say that Paul was wrong? Or the way I would frame it is, if Paul were here today, would he say something differently? And I would say today, Paul would look around and there wouldn’t be patriarchal tribal elders, in western culture at least, who have been endowed with status and power in a society. And so he certainly would not have helped create such roles and then men must be the only ones who could be in them. Rather he would say, if women are out there in the culture being given authority and entrusted to have certain social status, then you in the church better be willing to give women that same status. That he would have been saying that to not do so would have been risking your reputation as church.

[transitional music]

Nate: Okay, so what we’re reading here, similar to other passages we’ve looked at with Paul, is not him giving his critique of the whole elder system, patriarchal elder system that already would have existed in the Greco-Roman world that he was in. What we’re seeing is Paul working within that to say, “Okay, let me put some constraints on your power, let me put some structure around the power that you have, because that’s happening in the church too, and so I care about it. And here’s what that will look like to take this thing that already exists in your culture, these patriarchal elder-people and put some boundaries around it for the church and give some instruction for the church.” That’s what we’re reading, not Paul laying out what an elder is in the church necessarily.

Tim: Yep.

Nate: So explain to me the deacon piece, then. Was a deacon a thing that existed in the culture as well? Like an elder, overseer, I kind of see that, like these heads of the tribe kind of people, but then why this other role, deacon? That doesn’t, did that exist at the time too, and then he’s saying, “Here’s how I want to put constraints around that inside the church?

Tim: Great question. Okay, so part of the reason I tried to be as clear as I could up front as to where we’re going is this quickly gets into deep, muddy, complicated waters, which get into translation history, different words, how they’re used in different places. And it’s a long study, it’s another one of those where I’ve got pages and pages of notes. So I’m going to try to simplify this.

Nate: Okay, so give me, yeah give me just a quick overview of that. What do we need to know?

Tim: Okay, the quick overview is that ‘elder’ is very clearly a word that simply means old person. Okay? It just means old person. Old man. And it’s also a word that’s used so thoroughly throughout the Old Testament and in Jewish culture that it very clearly entailed certain communal, societal functions, okay? It was a well-established term for any Jew. And so what you see when you read the book of Acts, and I wish people would point this out more, you see Luke simultaneously writing in Acts discussing the Jewish elders who are opposing Christianity. Right, they are Jews who have trusted that Jesus is the messiah, they don’t think He’s the messiah, they want to put down Christianity, and so they just get called elders all over the place. They get paired with rulers and the chief priests and the teachers of the law. So you’ll see this, “And the elders and the teachers of the law came, and they did this, this, and this, and Paul said this to them.” Right? And then you’ll see Acts talking about the elders and the apostles, talking about Christians in the church using the same word. So you have the same role and function in the same Jewish society that’s trying to put down the Christian wing of Judaism and you have that same word functioning within the Christian sect of Judaism. And nowhere throughout the New Testament does Paul ever stop to say, “Hey, by the way, I’m going to use this word from here on out to mean something totally different than how you’ve been using it your entire life.” In other words, it’s an incredibly common term, it’s a loaded term with particular meaning. And so this isn’t really an argument from silence. What I’m saying is—

Nate: He even says it right at the beginning of chapter 3, “Here is a trustworthy saying: Whoever aspires to be an overseer desires a noble task.” He’s saying, “Hey, we all have this saying that we know of,” you know? This is a common thing that they’re used to.

Tim: Yeah, so even here in 1 Timothy 3, we read it as if Paul’s giving an outline for what an elder or overseer or deacon is supposed to do. He’s not! It’s assumed what these people do and why they are given this title or why this word is the right way of describing their function in the community.

Nate: This is probably why we don’t actually know, it doesn’t tell us in here what they’re supposed to do outside of to teach. Like you were saying even with the women that we allow to be deacons, we say, “Okay, they can be a small group leader,” even though it doesn’t say any of that stuff in here. It’s because, like what you’re saying right now, they already knew what these people do. It wasn’t that. He was putting constraints around the power that they have.

Tim: Yeah, I think that’s a good way of summarizing it. So real quickly I’ll summarize this a bit and then I think we need to do a six minute sidebar. So we’ll spend more of our time exploring the background to the word ‘elder’ and I think what that role meant, but ‘deacon’ is not a popular, loaded term, but it’s still once again a completely generic term. Deacon just means servant. The Greek word here is diakonos. Deacon is basically just a transliteration of the Greek word, which is a very common word and just means servant. So okay, here’s where we need to have a sidebar is talking about translation and words and where we’ve alluded to on the podcast before is talking about how translators are interpreters, and therefore they’re biased like all of us have our biases. And therefore there are theological biases written into our translations that are meant to, intend to affect the way that we interpret these texts. And part of the reason, I’ve said, that we can’t help but read the New Testament and think that Paul is a sexist, patriarchal complementarian is because so many—I’ll for now just hold off on the word sexist and patriarchal, but say so many complementarians have believed that was the right interpretation and therefore they’ve tried to help us see that as the right interpretation by translating the text in a certain way. So we point out the ESV was the most extreme of these, which was outright from the get-go an attempt to put together a complementarian translation of the Bible with an all male translation committee. But here’s where I’ve gotten flack, is people say that’s too far. I’ve had seminary professors say, “That’s too far, you can’t say that translators are misleading.” And I think I get that people are scared that everyday will lose trust in their English translations and stop reading their Bible or stop trusting their Bible. But I just think that thing is keeping us from actually being able to understand this thing better than it is.

Nate: Well, and can I just say, people are losing trust in their Bible and are stopping to read it because those things are there. Right? Because those translations are, it was an all male translation of the ESV people are not… you know what I’m saying? The fear that they have is actually coming true because of the interpretation that they’re holding onto for dear life. Not putting any motives in their head or anything like that, I’m just saying they are doing that and people are leaving the Bible, and that’s sort of the whole purpose of this show is to say you don’t have to do that. But you know what I mean?

Tim: Totally. Yeah. And the parallel, we’ve talked about this, is we’ve used the term ‘white theology.’ And so today after hundreds of years of white men having almost 100% of interpretive and translation authority in the western church, now any people that come along—feminists, womanists, black theologians, theologians from the Global South, and people of color—who have any interpretation that differs from the traditional and protected western protestant theology gets given a name like ‘feminist theology,’ or ‘womanist theology,’ or ‘womanist interpretations.’

Nate: ‘Black theology,’ yeah.

Tim: Yeah, or ‘liberation theology,’ right, which then like we just saw in the Social Justice Statement, if you can give something a title that says it’s not just theology, it’s ‘such-and-such theology,’ it makes it really easy to convince thousands and thousands of Christians that that stuff is heretical, foreign, and needs to be wiped out. And if you keep any adjective from in front of your theology and just say you’re doing theology, or even better, you say you’re doing ‘faithful, biblical theology,’ instead of saying, “Hey, by the way, we’re doing white imperial colonizing theology, and you can choose between ours and someone else’s”—

Nate: Yeah. Can I just say real quick: if you saw the Social Justice Statement that came out this last week and you were troubled by that and you need some help processing that, we recorded some thoughts on that. And we published it as an episode just for the day, and we still have that if you want to hear that, so just email us and we can send that over to you if you want some help processing that. Alright, continue.

Tim: Anyway, I paint the parallel to just say that we all are biased human beings, and all reading is interpretation, but also all translation is interpretation, and therefore all translation is biased. That doesn’t mean it’s evil. That’s just a fact.

Nate: What about the whole, “God was guiding these translators to get us to what—” you know what I mean? The whole ‘inspired Bible’? Isn’t that a process? I know this is a longer conversation, but I think that’s sort of the perception that we have, that God was guiding these hands and guiding the pens that wrote it, and then the people that decided what was supposed to be in it, and then the people who decided how to interpret it into all these languages. Isn’t that all part of the ‘inspired’ part of this whole thing?

Tim: Man. Now you’re making me want to have a longer conversation.

Nate: Which we are, right? We’ve been talking about doing a What is the Bible? kind of conversation, like what do we with this thing, right?

Tim: Yeah. And we’ll get into it in more detail. For now I think you’re spot on, one of the parts of the package that we have called inerrancy, biblical inerrancy, that protestants have made up in recent history, I actually think does state or imply, I’d say probably ‘imply’ is the truer term, that biblical inspiration, or God making sure that everything goes as He wants it to with the process of producing the Bible, that that has actually extended to modern English translators. I think a lot of people would, if they wouldn’t say it explicitly, that’s kind of how they’ve intuited it. And so the same idea that there can’t be any mistakes in the original writing of the Bible, there also can’t be any mistakes in our English translations. But here’s the thing: we don’t have a singular Bible. There isn’t a singular Bible in existence. We have multiple texts. That is just a fact. There are multiple texts of the Old Testament, there are multiple texts of all of the New Testament passages. The fact that we have multiple texts is actually part of how we know that these are reliable texts and they aren’t just made up by some crazy people. We have multiple versions of them that corroborate them. It’s part of why the Dead Sea Scrolls was so significant, because we found additional texts that were older than our original translations and copies that we were using for our modern English translations that we realized, actually they weren’t as different as we were scared they would be. They were pretty close to what we had gone with the whole time, and so it showed, “Hey, what we have is actually pretty accurate!” But not a hundred percent. Never a hundred percent. There are always differences in texts, so there is an entire field which all of biblical scholarship stands on called textual criticism, which is the job of looking at all of the different texts that we have, comparing them one to another. Which by the way, hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of scholars are still doing this with all the scrolls that were found at the Dead Sea. Going through them comparing different texts, for instance the dozens and dozens and dozens of different Hebrew versions of Isaiah, but then copies in other languages. And based on the acknowledgement and the assumption that all people are biased and all translators and even copyists will always be tempted to pass the text along in the way they think it ought to be interpreted, scholars, textual critics, they start with that point. That’s the basis, and they say, “Okay, this is what people do.” And then based on that, they go, “Okay, if this text has a word here and this text doesn’t have a word, is it more likely that text A added that word later, or is it more likely that that text was earliest and text B actually removed that word because it didn’t like it?” That is what textual criticism is in a broad summary, is literally saying, “We’ve got a bunch of texts out there. The best way to figure out which are the oldest, hence the most authentic originals, is to study how people translate texts into their own interpretive world to suit their biases.” And also, and this is huge—

Nate: I’m guessing this happens with lots of books, too, not just the Bible, right?

Tim: Yeah, yeah sure! But people don’t care nearly as much about a lot of texts. And—

Nate: Right, my point is that these practices, it’s not just something we had to develop just for the Bible. This is something, this field exists for just study ancient texts.

Tim: Correct. Yes. But the irony is that people, pastors and whoever else, are scared to tell Christians this, that there are multiple texts out there, because it’s going to help people lose their faith or whatever. The fact is, we have more copies and more versions of biblical literature, far and away more than any other literature and texts out there! And they’re remarkably well preserved. It actually, all of this evidence, the fact that there are multiple texts is actually something that gives people confidence that these are reliable texts. But the other piece, and then I’ll shut up on this, but the other piece is that the layering of translation from one language to another, from Old Hebrew to newer versions of Hebrew, from newer versions of Hebrew to Aramaic or Greek, those translations, as the people of God who were interested in these texts moved throughout history, as time went on and these texts got translated to be available for a new community, those translations are actually one of the best ways that good biblical scholars go back and try to understand what these texts meant to the audience when they were originally written.

Nate: Right.

Tim: In other words, one of the studies I’ve been doing recently is doing work in some of the Targums. Now Targums is just a name given to a whole bunch of Aramaic translations of the Old Testament. And you can look through, and scholars do all the work of trying to date when these different translations happen and see which are the oldest, which are the newest, but you can see some have all sorts of additions to them, some have changed words, or words just have multiple options in terms of how you translate them, and you can go back and look at how someone translated that in 300 A.D. And it’ll help you realize, they’re a lot closer to the original situation than we are, this is how they thought that text was written. So one fascinating one is, I can’t remember if we’ve mentioned this or not, this should be common fact for all Christians today: our Old Testaments and our modern Bibles are based on what’s called the Masoretic Text, which is a copy of the Hebrew Bible by Jews towards the end of the first millennium A.D. after hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of years of conflict between Jews and Christians. It is well established that the text itself is copied in a way, in many places, to downplay the idea of a suffering messiah. There are reasons why so many Christians today struggle to see messianism, or see the Old Testament as somehow pointing to Jesus. It’s because we’ve done our modern translations based off of a text that was biased to be less messianic. And the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the text that most of the New Testament authors were reading in their day, is exactly the opposite. They saw messianic clues everywhere. So you get all sorts of different words in translations. For instance, the Psalms, I learned, in the Septuagint and some of the Targums, literally say, “These are psalms about the messiah.” That’s the heading. Our headings in our Bible are like, “This is a song for David to be played by the maskil.” So my point is our theology is built on the fact that translation bias exists, and acknowledging and trying to understand it is literally the starting point for understanding what the Bible’s trying to say. So pretending that it doesn’t happen or claiming that my claim that it’s there is somehow unfair to modern translators is actually getting further from understanding the Bible.

[transitional music]

Nate: And I’m guessing that that’s kind of one of the keys for this 1 Timothy 3 stuff when we look at the words ‘deacon’ and maybe even some of the gender words that show up there? Is that right, or no?

Tim: Yeah. So this is one of those that just makes me scratch my head. So again, the word ‘elder.’ It’s the word presbuteros, which is where we get the word presbyter, like Presbyterian. That’s the reason that word is carried on. That word just means old person. And ironically, the translators have tried to help us by translating it some places as ‘elder’ and other places as ‘old person.’ Because they think they know as translators in which places it has certain connotations. And again, I’m not saying that’s evil. All translators have to make interpretive decisions on what passages mean in different places. But just look for instance, in the same text in 1 Timothy 5:1, the same word is used, and importantly as a part of the same logical mindset which Paul’s in. The same word is used, and the NIV translates as ‘older man.’ So it says, “Do not rebuke an older man harshly, but exhort him as if he were your father.” Literally the exact same word in the Greek. But just a couple verses away, for instance, in 1 Timothy 4:14, it says, “Do not neglect your gift, which was given to you through prophecy when the body of elders laid their hands on you.” But then a couple verses later it says, “Do not rebuke an older man harshly.” The point is, the translators think they know that in some places Paul is using this word to describe an office. So actually another little bit of evidence for this, if you use Logos Bible Software—I know most of you probably don’t, I do—there are these fancy schmancy Bible study tools that’ll show you kind of which connotations words are using in different places. It lists one of the ways that the term presbuteros is used in the [New] Testament is ‘as a Christian office.’ What is that? That’s an interpretation that what Paul is doing in his letters is establishing church hierarchy and offices. And then it’s trying to help get that interpretation to us readers by writing it in, okay? If they’re right, no big deal. But the fact is, they are forcing us to make an interpretive decision that we don’t even know that we’re making, right? And again, that’s why I’m saying it feels like that’s the only choice. Why? Because it’s been written in! It feels like we have to see these as positions or offices that Paul’s establishing because that’s what the translators want us to feel. So the other one that makes me feel even crazier is the word ‘deacon’ is literally just the word servant. And what makes this all more exasperating is, so in the history of translation in the Christian world, you went from the Greek and Hebrew of the New Testament and the Old Testament to then Latin. One of the first big translation projects was the Latin Vulgate by the dude named Jerome. So then you have this whole extra history of Latin language that’s affected things. So you actually still have today, in 2018, three different translations of the word diakonos, same words in letters written by the same person. And even in the same letter you have that word translated as basically just kept in the Greek and interpreted as ‘deacon. So it’s not an English word, that word doesn’t mean anything, it’s a Christian title where you make it sound like a title by keeping the Greek word as if it’s a specialized term. But then you have ‘minister,’ which is the Latin word for servant, and then you have ‘servant.’ So in Matthew 20 when Jesus says, “The greatest among you must be your servant,” that’s the word diakonos.

Nate: Oh.

Tim: But then here our translators have said, “Oh no, this is an office called deacons.”

Nate: Helped along by the titles at the top. Right? “Qualifications for Overseers and Deacons,” it makes you feel like you’re looking at here’s how to structure your church.

Tim: Exactly. It all feels like that’s the only way to read it. So when it says, “In the same way deacons are to be worthy of respect,” I just go, “Hold on!” Why are we reading a word that’s still in English? It hasn’t been translated! Deacon is not an English word. “In the same way servants are to be worthy of respect, sincere, not indulging in .” “A servant must be faithful to his wife.” So here’s my point: in these titles you have one is this overseer, which again gets lumped in to this elder, and there’s a whole world of background study I’d love to do on this overseer word and show the feminine and lowly, basically housekeeper, caretaker background to that word. This is not like supreme archbishop ruler man, this is like a humble title that Paul’s using.

Nate: Right.

Tim: And then the other one literally is servant. So here’s the last piece, I’ve got a bunch of notes, I’ll just have to blast through this. Throughout, from chapter 3 through chapter 5, Paul is consistently talking about two different age groups: old people and young people. And what you see, so for instance down in chapter 5 he talks about widows, and he basically gives different advice to old widows as he gives to young widows. And in chapter 4 is when he talks to Timothy, and he says, “Hey, by the way, Timothy, don’t let anyone look down on you because you are young, but set an example for the believers in speech, in conduct, in love, in faith and in purity.” So here’s why I bring that up. What it looks very apparent to me that Paul is doing is he’s saying that there are basically two classes of people in the community. Not based on his own imagination, just based on the way Jewish clan societies arranged themselves, which are societies just like most societies before western enlightenment world, which gave honor and reverence to the older people in societies, whether it’s matriarchal or patriarchal. The oldest head of the household, the oldest remaining member of the family, was the one who would just automatically be given esteem. Clout is the best word I’ve been able to come up with. Doesn’t necessarily mean power; it’s that they are respected. And the younger people are to show them respect. And it actually seems to me like this differentiation based on age is one of the only status differentiations that Paul honors in all of his theology. So we’ve talked about how he looks to the gospel and says that Jew/Gentile is nullified, there’s no racial differences. There’s no differences between a slave master and a slave, they are made equal. Basically all of these different groupings on the social ladder. But Paul basically leaves space for communities, Christian communities, to honor the old members of their community, old, respected, as kind of the heads of the tribe, just as they were in Jewish society before they started these new communities. And so for instance, Timothy is an apostle with Paul, but Paul never calls Timothy an elder. His whole point here in chapter 4 is if Timothy does a good job—and here’s another one of those translation pieces. Verse 6 in chapter 4, “If you point these things out to the brothers and sisters, you will be a good minister of Christ Jesus.” That’s the same word, diakonos, servant or deacon. So what Paul is saying is Timothy’s a young dude. He actually has tremendous authority, he’s going around as an apostle teaching people the gospel. But he’s not going to be an elder. Why? Because he’s a woman? No, because he’s young! You don’t call young people elderly! I actually think a better translation for the word elder, if you’re going for what the closest English word would mean, is the elderly.

Nate: I was going to say, it’s the exact word that it is.

Tim: [laughing] Exactly! But all I’m saying is, stop painting all of this title office language on it, and you can start to see there’s actually some cohesion here. There’s some explanatory sense. So all that to say, is I think what’s happening is Paul is acknowledging that just as in Jewish communities, which were patriarchal—I’m not saying this isn’t patriarchal and sexist. It is. Paul was working within a Jewish culture and a Greco-Roman culture that was completely patriarchal. So my point in saying that, there was no part of his imagination that communities preexisting before he and other people like him with Christian theology got there would have expected to see women as matriarchal heads, as the top of the clan. He assumed that these would be men. But then what we go on and see in places like Romans 16, is Paul is empowering people to be apostles, lead churches, prophesy, all of the stuff. Paul doesn’t lay down any regulations or constraints based on gender. He’s just assuming that they’re there. So I actually think what’s very fair to assume, you see in Acts and you see here is Paul says elders need to be appointed. But in other places it doesn’t talk about appointing elders. The assumption is basically if there was an elder in a Jewish community, or Jewish family, large family, and that family converted including that elder, that person would be the elder of the church community. But if that elder doesn’t convert and you’re left with people who are actually wanting an older figure to help them understand what the heck they’re supposed to be, then Paul and Timothy and others go around helping those communities find such people, but they do it always, just like in the Old Testament, based on those people already having the respect of those communities. In other words, they’re appointing them, it’s the same word ordain. They’re just saying, “Hey, these guys you look to? Yeah, look to them and give them some respect as old people.” But basically, and we’ll get into the details later, my thought here is you basically see in 1 Timothy 3:2 general categories of people based on age, age and clout. You have the smaller group, which is the elders who are basically the heads of the tribe, and then you have everybody else who are servants. And Paul refers to himself as a servant constantly. So in that way he’s not at all applying a rule of masculinity or depriving women from being in any of these roles. He’s speaking to societal communal functions that would have been held by men, and asking the men to essentially limit their power by applying themselves, by applying a harsh ethical constriction to them. And elsewhere we see Paul constantly honoring women in all sorts of positions of status within the church.

Nate: Alright. There’s 1 Timothy 3. And we do have probably another episode on the gender series. I’m not going to promise. We promise stuff on the show sometimes and then we don’t come through, so I’m just going to say, we’re wrapping the series soon, potentially one more, maybe more. So come on back. If you want, we had someone ask this week about discussions for the show. If you want to discuss, right now we don’t have a message board or anything like that, a forum. If you want to discuss, each episode on our website has comments down below. You can talk to each other and reply and kind of talk in line right there on each episode. So if there’s an episode that really stuck out to you, go ahead and share a comment there. Or you can just email us too if you have a thought. And then ask questions. We love to hear those and it kind of shapes what we do with the show. And we’re going to start working them in to the end of each show. And the last announcement, from the beginning of the episode, if you want to take part in some conversations, pretty lowkey, informal conversations that we’re going to be having in Portland on November 11th and 12th, you can sign up at almostheretical.com. And we’d love to see you there and meet you. Alright, we will see you next time.

Tim: Peace, y’all.

[One Mic by Nas playing (yet again)]