Summary

Did you used to picture flying away to be in heaven? Or, maybe you’ve thought of new creation as what heaven is. After spending 3 episodes talking about hell, Nate & Tim work to complicate the conception of heaven, in keeping with the biblical writers.

Transcribed

Tim: Okay, welcome back! Nate, what are we doing this week?

Nate: We’re talking about heaven, maybe? Okay, but first, first, first, first. We just recorded another episode that you’re not going to hear if you just subscribe to Almost Heretical. This is a second podcast we’re doing, and it’s only for supporters of the show. We just recorded it, we’re calling the show Utterly Heretical, because we don’t really have much filter on it. It’s raw; it’s unedited. It’s… Tim, what is it?

Tim: If Almost Heretical has created a slippery slope like your parents and pastors are afraid of, Utterly Heretical is a push that is a race to the bottom of that slippery slope.

Nate: [laughing] It’s really not that bad!

Tim: So if this has you teetering on the edge of hell and eternal torment… Nah, it’s really not that.

Nate: It’s not that bad. But we do say—

Tim: It’s pretty fun, though.

Nate: It was, I think it was probably the most fun we’ve had recording in a long time. We do say more things on there that we don’t say on here. We tell more stories and more parts of stories that we don’t always get to. Some of it’s just time, we don’t have a lot of time to get to things on here, it’s a little freer. Anyways! You should go listen to it. Utterly Heretical Episode 1 is live now. You can go to patreon.com/almostheretical, and find it there.

Tim: Cool, but here we are.

Nate: Okay, so heaven. We just talked about hell for three episodes, but there’s the other place: heaven.

Tim: I did kind of feel like, you know, I already struggle with being pessimistic and cynical. Like you can’t only do a long series on hell and not even mention the good stuff, right? We should at least have some optimism. It’s very classic of me to just focus on the bad.

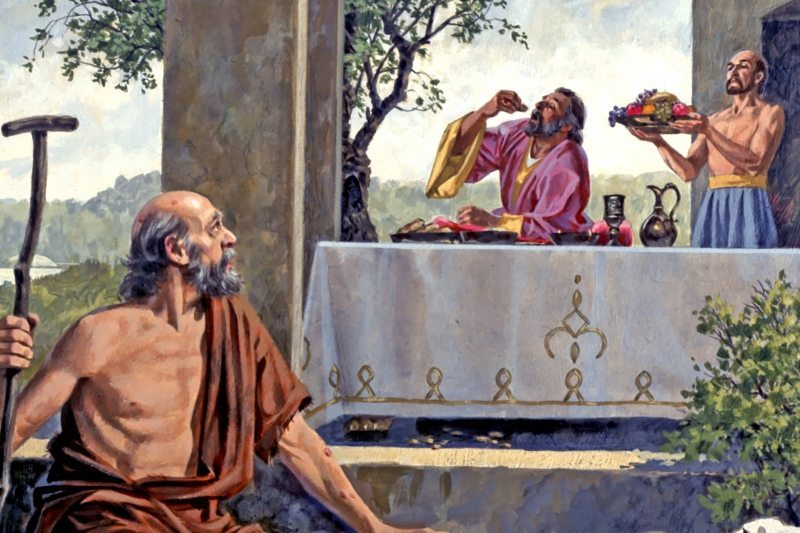

Nate: Well, I think I mentioned this in part 1 I think, but I really most of my life didn’t hear so much about hell. We heard some crazy stories from people who were completely traumatized with pictures of hell. I guess to an extent I was asking Jesus into my heart over and over again growing up, because I was afraid of hell when you boil it all down, but—boil it all down? There’s so many bad hell puns that we’ve discovered when we try to title these episodes and as we talk. But mostly it was a positive experience of this place you do want to go, heaven, and what that was. Not so much what it was going to be like, but just that there was this amazing perfect, perfection, this place that you did want to go to. Oh, that reminds me, I want to talk about perfection, the idea of perfection and returning to the garden and all that stuff. We’ll get to that, but you know what I’m saying? I think there are a lot of people out there who didn’t necessarily have traumatic experiences of depictions of hell that were given to them and that’s why they were trying to be saved, but it was this positive experience of this good place that you can go. And I’ve seen that change over time. I think what is talked about a lot, thanks to N.T. Wright largely and then guys like Tim Mackie and The Bible Project is even in kind of Reformed circles, hearing and talking more about heaven on earth and new creation, which I think is a lot more of a helpful explanation than kind of this picture of being on clouds with harps that I think some people had in the past. That was a lot of stuff. Tim, help me out here!

Tim: Uh, well actually, so we recently announced to some of our patrons that we were going to do the heaven series, and one of our supporters, a guy named Benjamin, sent us a message, and he said something that I thought really apt. I hadn’t really thought of it this way. But he basically said pretty much like, “Okay cool, you guys are going to do a heaven series, but I don’t really care.” And his point was, “I cared about hell because of how toxic so much of the stuff, the ideology and the preaching around hell has been, it’s terrified people, traumatized people, and scared people away from Jesus.” Heaven, on the other hand, isn’t as important, essentially, to deconstruct and reconstruct because it’s not like that boring vision of angel babies on harps is scaring people away from Christianity. It’s more just kind of like a silly point. So for him he was saying that he’s interested in the conversation, but it’s not nearly as emotionally important to him. So I totally understood that, although I hadn’t really thought that yet. But I’m curious, Nate, does that ring true to you? That thinking well about heaven, is that less important or significant than trying to start thinking better about hell?

Nate: Eh. Kind of, but I’ll say this. Largely what I was doing in ministry was telling people that we’re leaving this place. So here’s another toxic view but that has a positive spin to it. Not that earth is going to burn so much, but just that we are leaving this place, and I’m thinking all the time about heaven, “Eternity on my mind,” you know? Just so focused on this other world, I literally pictured it like this other world that I was going to, and so my time here until I take my last breath was all about telling people about this other place that they could go. And I think there’s something psychological there when you are really checked out of this world, the actual experience of what you’re in right here and what you can see and the people you’re around. And Alex and I were talking about this, on how we didn’t even really focus on our own personal well-being at all, like learning more about ourselves and who we are, and things like therapy and becoming better versions of ourselves, because we were so focused on this other world, that we were going to magically become these other types of people and all this stuff. And I think that it really is toxic. We were realizing how that has set us back on our journey of health as human beings personally and then being able to even have anything to offer other people around us because we were so focused on it. So I think there is a toxic—obviously hell, when you’re talking about that torment and telling people that’s what they’re going to experience, I get the trauma there. But you see what I’m saying? There is an aspect of that that is present even when we’re talking about something like heaven.

Tim: Yeah. I think what I hear you saying is that the most toxic element about various heaven theologies was escapism, that this place is all just going to burn up, and so it doesn’t matter what we do in this life. Both, we mentioned the recycling and destroying the earth example from our past ministry world, but then you’re talking about even just neglect for personal well-being, health… self-care in the modern vernacular. Is that kind of right, that that piece, basically that this life doesn’t matter, ends up actually being incredibly toxic? In the world you and I come from, I know it was really close to the sort of martyrdom, messiah complex thing, where the more you were essentially self-inflicting, not self torture, but basically self-inflicting non-well being for the sake of the gospel, that that was the kind of honor badge that we all were striving toward. It was like the medal we wanted to get. Which made it, you and I and our wives and families and close friends, we all had to go through many years of unlearning that so that we could actually learn how to take care of ourselves and each other, especially when we got married, right?

Nate: Yeah. Yeah, I mean, you couldn’t focus on yourself. That was sinful to focus on yourself and your needs and your emotional health and spiritual health. So yeah, we left that whole season just completely drained, so drained that we didn’t even know what was wrong. We didn’t even know what we were feeling, we just knew we were completely drained. And again, largely I think the focus was on heaven; it wasn’t on hell. What I was teaching on and what I was talking about all the time was heaven and this next life that we’re going to, and I think there is just something really harmful about that. It’s so disconnected from our human experience.

Tim: But because, it was harmful because it wasn’t at all integrated with understandings of what leads to good living here and now.

Nate: Exactly.

Tim: It was totally separate, so it actually exacerbated. You know, none of us are really good at taking care of ourselves or each other, we have to learn the skills to do that, at least I think that’s mostly true. And so especially when you’re young and we’re all in our early twenties, just trying to not eat microwaved food all the time is a hard discipline to get into, let alone when we start to get to the age when we need to start processing our childhood and deep trauma and wounds and stuff like that. None of us are very good at that, and it’s hard, so then if you have a theology that is essentially exacerbating that by saying, “Just pretend that’s not there, ignore it, don’t focus on that. That’s all worldly stuff that we’re not supposed to care about,” I totally see the toxicity in that. But I think more what Benjamin’s point was was if what we’re trying to do is sort of, how should we imagine the concept of heaven, or the piece where it’s like how should we try to figure out and understand what the biblical authors had in their imaginations when they were imagining paradise or the new Eden or the new creation or whatever, if we get those ideas wrong, it makes God seem maybe boring or trivial or non-important, or like a hovering helicopter parent. It doesn’t make God seem like a monster in the way that eternal conscious torment and various depictions of hell make God seem, right?

Nate: Oh, yeah, totally. Totally.

Tim: It seems like in that regard, there’s a little bit less at stake.

Nate: Totally.

Tim: So we weren’t actually planning to do a series on heaven pretty much for that exact reason, right? We wanted to do a series on hell because we’ve heard so many stories and have had so much experience with the trauma around ugly theologies related to hell. But then I don’t know, we were like halfway through the hell series where I at least started to realize as much as I pick on and try to undo the way that we’ve arranged various ideologies and pieces of Christian theology in our head, one piece that I think is kind of okay, that for once I don’t want to pick apart, is the connection between the concepts of heaven and hell. Like that these are integrally connected ideas, and so to talk about one, you kind of have to talk about the other, or to think well about one. These are two integrally connected ideas; they’re not exactly equal mirrored pairs, but some of the questions that lead to the concepts of heaven are related to the same questions that led to the concepts of Hades, Gehenna, Tartarus. So what we tried to do in the hell conversation is essentially to re-complicate the conceptions. It had been overly simplified, even just in the word hell, it’s a mass oversimplification. So we tried to back up, expand it, show how there’s multiple ideas lumped into that one conception, and then there’s disagreement, even, of different pieces of the ideas. And by doing that the hope was we could sort of liberate ourselves from some of the uglier pieces of the hell conception. And I think what we’ll find is that actually when you compare the way we do something similar with heaven, is it’ll be really interesting the way that, I’ll argue, you can’t think about heaven without thinking about some of these other things and ideas that are integral to the concepts within the scriptures of heaven. It’ll be interesting to see which of those we’d already said are completely connected to hell and which of them will feel totally brand new. For instance, what we’re going to have to talk about if we do a deep dive into heaven is how the various biblical authors conceived of human beings and human bodies, and then that’ll quickly take us into this crazy world of Old Testament, New Testament cosmology, where there are gods and these spirit beings, and then we are the earthling, terrestrial beings, made of the dirt of the earth. And there is a war relationship happening, this war for power going on between these two species. But one in which we somehow have a future of becoming no longer earthly beings, but essentially extraterrestrials [laughs].

Nate: Oh my word. Okay. [laughing]

Tim: Yeah, we’ll get there.

Nate: Time out, time out! [laughing in background] Okay, um.

Tim: [laughs] Hold on. My point is—we’ll get there, you can unpack that, you can call me an ultra heretic, whatever. I joked that I wanted to call one of the episodes, “Maybe the Mormons have it right.” Because there really is a lot going on in terms of glorification, deification, even just right in Paul’s plain writing. My point is, we didn’t talk about any of that when we talked about hell, right? So if I’m right in the sense that we need to talk about those things to talk about heaven, well why didn’t we have to talk about that in our conception of hell? And I think what it’ll do is show, oh, actually maybe some of our conception of hell was even more oversimplified than we thought. If this is how broad and complex the heaven conversation is? For instance, another example, we’re going to talk about heaven as a revolution and basically all about power and a reversal of power. Well, why is it that we didn’t talk about hell in that way? And I think what we’ll see is we’ll learn more about hell as we talk about heaven; learn more about heaven as we go back and talk about hell.

[transitional music]

Nate: Okay, that sounds a little less crazy. The other stuff you started saying reminded of the conversation we had in Utterly Heretical, the Patreon-only podcast, about whether or not we even believe this stuff and like, getting to, I guess, a better picture of what the biblical writers are saying, what they probably had in their head. And then I asked Tim on our other show how much of this do you actually believe, and that was kind of a fun chat, so go check that out, but—

Tim: Well, and I’ll just say up front, if you want believing in heaven to get easier or to remain easy, then I would say go get any one of those now-rescinded books about stories of kids going and seeing heaven and coming back, that I think all of them have basically been proven false at this point, or proven manufactured. Go read those and stop listening to this podcast, because this podcast is going to make you hopefully have some more beautiful, interesting conceptions in your head. It will make things more complicated, and I think at the end of the day, it’ll make it harder for you to just say, “Yeah, I believe that.” So that’s not really what we’re in the business of. I’m not trying to knock anybody off of their belief pedestal.

Nate: That’s… we’re 59 episodes in now. If you’re here, I think you want to go on this journey with us, so I think we should do that.

Tim: Yeah. If the word ‘extraterrestrial’ in the first five minutes of the podcast is scary enough to get you to leave, it’s probably best you just abandon ship now. That might include you, Nate. And then it’s just me here.

Nate: [makes sound effect of… spaceship flying off?] Okay, okay. So those that are still here I think want to be here. Tim, where do we need to start when we’re thinking in a fresh way about heaven?

Tim: Yeah, I… I don’t know. This is another one where I’ve got fifty pages of notes, and it’s very hard for me to get down to what’s the best logical order of this. So some of this I’ll just say bear with us as we bounce around, but for me, I’m a big picture person, and details are fine and interesting at times, but I need to have a big framework to fit them into, and one of, before I started getting frustrated with evangelicalism and power dynamics and abuse in the church and all of that, some of my early grumblings with the kind of theological training or even just the kind of theological culture of church that I spent my late teenage, early twenties years in, was that we didn’t really ask good questions. And asking good questions, or figuring out what the right questions are, or what the best questions are, or even figuring out what the questions that the biblical authors were themselves asking and answering, that wasn’t really a part of it. We skipped the questions and jumped right to the answers. So when it comes, to me when it comes to studying the Bible, or honestly when it comes to even just my favorite podcasts to listen to, storytelling stuff, is when you have a good question. A fascinating question, a profound question, an important question, a significant question. So what I like to do is back up and figure out, kind of like what we did with hell, what were the questions being asked by the biblical author, by the audience, by the culture around, by the Jewish people? What were the questions they were asking, either aloud, or just everybody’s kind of thinking these things, that ever led to for instance, using Gehenna, this town dump on fire, as a metaphor? Like how did that ever come about? So where I would like to start is basically trying to at least brainstorm some of and list out some of the biggest questions that heaven is an answer to. And again, this’ll sort of shoot us right into seeing it’s much more complicated. It’s not just one question, it’s many questions. And “heaven” again, just like the word “hell”, is an oversimplification that for us is going to be a box that holds many other ideas, ideas that relate to paradise; you mentioned perfection, we’ll kind of get there later; eternity, this sort of timescale where things last a really long time; Eden and a return to this garden paradise setting; the temple. All of these things are different facets of what we’ve just called heaven. So let’s just start with some of the questions. I’ve got a list, but—

Nate: When you said eternity and thinking about that. It made me think, did your head used to kind of like, break as a kid when you tried to think of eternity? When you tried to think of something never ending?

Tim: Oh… You know, I’m tempted to say yes, but I think it might just be because I’ve heard so many people share stories of that, like I might be projecting those stories onto my childhood. I actually can’t remember that. I do know I was, like many people, as a kid, and again I didn’t grow up super entrenched in church culture, as a kid it was just all very boring. It wasn’t as much like, “Oh, let me figure out the timing and mechanics of this,” it was just boring. It was more of a general sense that there’s a good place and a bad place. What I… Part of this conversation that I’m excited to get to is how many Jewish thinkers, rabbis and even some of the biblical authors, were evidently—we can see this—having dialogues about the timing dynamics and the various philosophical issues that come about, especially with the concept of resurrection. That piece is fascinating to me, as soon as you have a concept like neverending time, if you think hard enough, you end up finding all sorts of problems. Like things that can’t work. Like just throughout, do we still eat food? What happens if you get a cut and it doesn’t stop bleeding? You get into these questions, and you can see some people have tried to answer them, some people are like, “Uh, just don’t think about them.” I do remember, however though, getting in a fight of one of the more embarrassing, this might be top of the list, most embarrassing actions taken back when I was in my totally, police the borders of orthodoxy in a staunch conservative mindset, back when I was writing papers on hell. I totally bought into the idea of heaven as simply the place where holy people spend time with God, so there was no world around us, no things. So there certainly weren’t going to be pets. And I remember [crosstalk]

Nate: Oh, dear.

Tim: Actually you know her, Tiff. One of our good friends who lives here in Bend with us now. She’s been a big animal person, and had I think it was a cat back in San Francisco. And I spent weeks trying to convince her that there was no room in heaven for her cat. [laughs]

Nate: I remember talking to you about that, yeah!

Tim: [laughing] Do you remember this?!

Nate: Yeah! [laughs]

Tim: Oh, just so despicable. A) because now I think that’s exactly false. Like if there’s no room for cats, there’s no room for anything. Although, I personally have a bias towards dogs, but that’s neither here nor there.

Nate: I was going to say, cats are probably one of the last things getting in, but yeah, okay. Keep going

Tim: But like, that thing is the same reason people go on these Twitter-trolling rampages, and literally emotionally torture people to try to bring them into orthodoxy. I think her cat was sick or something, I can’t remember.

Nate: Oh, Tim.

Tim: Her cat might have died! And she was single at the time, so this was a very connected cat, like a very emotionally significant cat. And my whole point was that basically all of her emotional connection and her sympathy towards that animal were not only wrong or false or illogical, but were unChristian and unholy. So I was trying to get her to not give a crap that her cat had died, or her cat might have been going to die, because of how stupid my conception of heaven was. I do remember that.

Nate: Oh dear. That’s pretty bad. I was just going to say that when you mentioned, what is it going to be like, are we going to eat food? I remember a big one for the church that I started, we were talking all the time about how there’s not going to be marriage in heaven, right, because of that verse. And how that means that in order of priorities, you need to focus, don’t focus on your marriage, don’t focus on your family, but focus on the mission of God, of getting people saved to this place where you’re not going to be married. So marriage was a very practical thing in our group, you needed this to be better for the kingdom so that you could save more people, but don’t focus on the actual dynamics of your marriage so much, because that’s just a distraction from saving people for heaven. But it was just this weird circular thing. But anyways, I do remember that.

Tim: Okay, another tangent and a whole series that I’ve had notes for for a while is one of the great hypocrisies in modern evangelical Christianity, embodied literally in the organization Focus on the Family in just its name, focusing on family, whose primary agenda is to reinforce essentially mid 50s patriarchal gender roles and family patterns. And especially engaging in a war against LGBTQ equality, and at the same time much of that world is what you just said, is simultaneously diminishing the insignificance of health and quality within marriage so that on one hand you’re basically saying, “The most important thing is to reinforce heterosexual marriage as the norm in the culture,” and at the same time, “What we need to do is diminish the importance of all of these people participating in heterosexual marriages, and them having any ability to do this thing well and healthily.”

Nate: Right.

Tim: Just crazy!

Nate: Right. Yeah.

Tim: Okay, heaven.

Nate: Questions.

Tim: If you were to try to imagine in your mindset, I mean you can include when you were a kid, kind of early stages, and then later years, the last five or ten years of your life, as you’ve thought about heaven, what would you say were the questions to which heaven was the answer?

Nate: Hmm. I guess the main one is where do the people who God loves, where do they go? What happens to them? What’s the benefit for following Jesus and being a Christian and all of that? I think that’s the main question.

Tim: Hmm. What’s the benefit? Wow.

Nate: Yeah. Well, yeah but then there’s also the other side of the benefit is Jesus now. I remember Brandi Miller talking about that a few episodes ago. And I remember a lot of that and teaching a lot of that, you know? “Don’t do this for any other reason, but for Jesus now. And then heaven is just more Jesus for all of eternity.” So there’s just definitely the benefit of your personal relationship with Jesus, I definitely taught that, but ultimately you’re making this trade-off. You’re choosing, like you said, you and I were very much kind of a part of what some would call a poverty gospel, like suffering for Jesus. Sometimes intentionally, often intentionally, putting yourself in bad circumstances, in negative circumstances in order to suffer for Jesus, because this trade-off you’re making is, “I’m going to suffer, I’m going to choose to suffer and beat my body now so that I can have this reward later.” We talked lots about the crown you’re going to get, right? I mean, yes, you’re going to give the crown up or lay it down, but it really was, an eternal benefit. I think benefit is a… you made me question it, whether or not that was an appropriate word, but I really think that that was a picture that I taught. It’s hard for me, honestly, to remember back too far, so when I talk on this show, I’m generally talking about what I taught in the church that I planted, but that’s sort of what I would have held to, I think.

Tim: Right. Yeah, and I don’t question heaven as “the benefit” or the point. I don’t question that that was it. I think it was just actually, it had been a while since I’d just heard it put that bluntly. You know? But you’re right, even if it was framed as, “Well, heaven is life with Jesus to infinity, in strong doses,” even if that was the way it was framed, that still is saying that heaven is the benefit. I think it’s easy to see, though, how clearly that question or that way of explaining the point of heaven can only exist within the world of Christian culture. Like within the world of, the religion has existed for a long time, and we’re explaining the value of the religion.

Nate: Explain that.

Tim: You know what I mean?

Nate: No, I don’t get it.

Tim: So that question is basically, “What is the value of being a Christian?”

Nate: Right.

Tim: “What is the benefit for participating in this religion?” If you just think about that, there’s no way that that question preexisted the religion.

Nate: Right. It has to have a reason for why this thing started in the first place.

Tim: Right. And I think we, most of us, have thought hard enough to know that the way ancient Israel and the ancient Jewish people was working was not like, “What is the benefit to being a Jew?” Right? You were a Jew, or you weren’t a Jew. So if you were to have come up with a conception of heaven, or say inherited through divine revelation if that’s the way you want to think of it, a conception of heaven, it certainly could not have been, “What’s the benefit to being in this religion?” It would have had to have been connected to other questions. So the first one, you’ve probably heard this, but the first piece of the question is the word heaven in Hebrew, it’s plural world—plural… In Hebrew, it’s actually a plural worl—[laughs]

Nate: Oh geez.

Tim: Okay. Apparently I can’t say “Plural word,” so we’re just going to say that heaven was a plural world, which is actually also true in Hebrew.

Nate: Usually I would edit that all up, clean it up, but no. It’s staying.

Tim: There you go. Coming to you straight. So it’s the word skies, shamayim. And that’s what the—

Nate: Is this like, “The heavens declare the glory of the Lord,” is it sometimes translated plural even in English?

Tim: Yes. Totally, sometimes it’s translated plural, sometimes it’s translated singular. And there is some justification for that, I don’t think it justified, but there is some justification, because as we’ll see, when… One question is, “What is up there when I look up in the sky?” If it’s sunny out and the sky is blue, what am I looking at when I see that big blue mass? If it’s nighttime, what is that that I’m seeing? What do we call it, but then also, what is it? What’s up there? We’ll get into some of the details of divine cosmology and this three-tiered earth, and how they thought the sky was the bottom of essentially another flat world, and that when rain fell it was because God had opened up the windows and water was falling out. So they actually thought they were looking at the bottom of a sea. Whether they literally thought that or they just decided that’s—

Nate: “That’s what we’re going with.”

Tim: Yeah. Totally. But so connected, and you’ll see pieces of this all throughout the scripture, is the connection of where does wind come from. We now have weather science, right.

Nate: We still don’t know.

Tim: Well, yeah. Well, we kind of know that wind doesn’t “come” from anywhere, wind is created because of temperature differences and moisture differences and all that, but then like I just said, where does rain come from? Where does lightning come from? What is sunshine? Where do these things happen? And so what you’ll see, there’s literally a conception, it gets repeated the word “storehouses” is typically the way it’s translated in most English Bibles. The storehouses of heaven.

Nate: Like there’s just a big tank up there.

Tim: Like literally, there’s storage rooms.

Nate: Like a silo?

Tim: Where God keeps the wind, the rain, the lightning, the sun.

Nate: Okay. Okay. I appreciate that! I appreciate it, actually. I mean, we’re talking, we have to remember this, we’re talking about a very primitive, as far as our culture today is concerned. And someone will be saying this on a… it won’t be a podcast, but something, in a thousand years someone will be saying something about that about our culture, but it’s a very primitive understanding of the world, and I appreciate. That’s actually, I think if we try to explain that away in the Bible, like, “That’s actually not what they thought, and they actually knew all along,” then we’re cheapening what these actual experiences of actual people. Okay, sorry.

Tim: Totally. Yeah someone will listen to this podcast and be like, “Tim actually thought wind was based on atmospheric pressure differences. What a fool, they actually believed that.”

[transitional music]

Tim: So basically, heaven equals sky. It’s the skies, but also we don’t have a conception of… in the recent past we literally transported human beings through heavens and realized we could get all the way up into outer space. And now we know what stars and stuff are, so we have this whole conception that we just can’t get away from of sky, atmosphere, ozone layer, breaking out of orbit, space, mass gravity, cold, darkness, all that sort of thing. They just had a broader general conception. But this is where you kind of get heaven as a place. What we’ll see later too, is there’s also, and it’s a place up in the skies. There’s also, merging with this is this idea of paradise connected to the Genesis stories of this paradise garden in this land called Eden.

Nate: Yeah, yeah yeah.

Tim: So there are actually some texts, especially some Second Temple texts, where you’ll have one author talking about heaven or paradise as in the sky and also some distance aways on earth, to the east, to the west. It’s a place that you could go travel to and find, and it can be conceptualized.

Nate: Oh, interesting.

Tim: So in one sense heaven is just this sense of far off place, inaccessible. It’s on earth, but it’s so far out, we don’t know where it is, we probably are not going to find. So you have stories of Enoch as a literary character goes and travels to paradise, but it’s here on earth, and you also have stories of Enoch going up to be with God in paradise in heaven. Anyway, another question, and it’s totally related, is where does God live? I think we’re more familiar with that question. Right, it’s like the Sunday School version, God’s up in heaven. But connected would that and never would have been separated is where do the gods live?

Nate: Gotcha. Yeah.

Tim: We have a conception that God is the only divine being. Again, we keep saying go back to the first ten episodes or so of the podcast. We’re going to actually recover some of that ground in this heaven series, so hopefully you don’t have to keep going back, but if you need an intro, do go back and listen to the basic conception, Jewish monotheism was not about there being one divine being, but about Israel, God’s people, only worshipping Yahweh as the utmost divine being. They believed there was a whole plethora of divine beings, the sons of God, elohim, these angelic beings. They’re not earth beings. So what are they? They’re heaven beings, they’re sky beings or spirit beings, we’ll kind of get into some of that. But the idea is there are two realms. There’s earth realm. And again, it’s hard for us to picture this because we know we live on a spinning ball of rock, and that then beyond us is massive amount of empty space and then stars and planets and whatnot, but to them it was basically a flat world. Underneath that flat world is the underworld, and above that flat world is basically the upperworld. So the dead go down to the underworld, to Hades. We when we’re alive are here as these earthlings. But then there is this second realm of non-earth space, which is basically the divine space. So that’s part of where you get these geographic, if that’s even the right word for it, spatial ideas of heaven, which are sort of how we think about it. We still sort of think of heaven as a place in the sky; we just know that it’s not literally just above the clouds, right?

Nate: Yeah. So where do we actually think it is? If you were to push someone on it, is it like a different dimension essentially is how we would talk about that? And maybe we don’t need to get into all this, but…

Tim: [laughs] Do you mean like, what would Ken Ham think? We should ask him!

Nate: Yeah, what is the—Yeah, he’d return our call. What is the—I probably still have his number, actually. So I used to be a producer of a Christian talk show in Los Angeles, California. Shout out to you, KKLA. And I had all, I still have, all the numbers for all the people that you potentially don’t want to talk to. So I think we should have a show sometime where we just call up random people and try to have a talk with them until they hang up on us. I have Dinesh D’Souza’s number, and I think that could be a bad and interesting conversation.

Tim: That could be the end of everything.

Nate: Yeah. So yeah, you’re saying this is literally what they thought. They thought this, this kind of reminds me of John Walton trying to understand what did the writer of Genesis, how did they conceive of the where we are in the cosmos? Maybe cosmos isn’t even the right word for their conception.

Tim: Right. And again I’m saying, yes and no about whether this is literally what they thought. My point is this is where the conception, for one it’s where the word comes from, so when we say heaven we are saying “sky.” That’s what we’re saying. So where did the conception of “sky” as the word that’s going to contain all these other concepts of what happens after you die and eternity and paradise, those things. The first couple reasons are that when you look up in the sky when you’re an ancient without modern science, you start conjecturing about what is up there, and part of that conjecture led to, “That is God’s abode.” That is where God and the gods exist and live. And so part of the conception of heaven is heaven is the divine house, that is the divine realm, the divine abode. Because it is the sky, and because sky is up away from here, and there are stars in it, which look like shining gods, essentially, and therefore that is where God lives. So there are these conceptions of God sits on His throne in heaven, and the earth is where He puts His feet, like the earth is God’s footstool?

Nate: Right.

Tim: That’s the basic conception. Now I don’t think anyone literally was like, “Yeah, if you go around this corner, two wagon blocks to your left, and turn around that hill and you’ll see God’s feet.” I don’t think it was that literal. My point is this was some shared conception, but loaded in here is that. So then when you get into some of the more religious connotations, one of the questions is similar to what you listed, what happens when I die? So this is one that we said is exactly parallel to where the idea of Hades came from, right? We see people die, and we know they’re not here anymore. They’re not talking, they’re dead, their bodies will decay, we’ll put their bodies in the ground to literally become the earth again. But what happens to us?

Nate: Is this where the idea of soul comes in too?

Tim: It’s totally connected, yeah. And again that’s part of why I say we’ll have to get into the question of what is, and related here to heaven, what is the nature of a human being? And that shows up on page one in Genesis. What is the nature of a human being? What are we made of? What part of us, if any, exists beyond death? What part of us is contingent on this body? Are we a body, are we more than a body, are we less than a body? All those questions are wrapped up. But where it comes to heaven primarily, and this is pretty close to our modern caricature, is when I die, does some part of my body or some part of myself live on? So that’s pretty close to our caricatures, there’s a body and a soul, your body dies, your soul floats up. You know, there’s even like the… was it All Dogs Go to Heaven? Is that the cartoon I’m picturing?

Nate: Probably.

Tim: It was like all these… It was the cartoon thing right, like the color would fade and the like, spirit ghost version of the thing would like float up?

Nate: Would escape out, float up

Tim: Yeah, you kind of know what I’m talking about?

Nate: I can picture it.

Tim: It was like… Oh no, you know what I’m thinking of? I’m thinking of Who Framed Roger Rabbit!

Nate: Oh! I maybe saw that one time.

Tim: Go back. It’s great.

Nate: I think I’m thinking of a video game, maybe it’s The Sims, where the character dies and you see the way they depict death was this kind of ghost, spirit figure floating upwards. I think it might have been The Sims.

Tim: Right. So okay, so that is exactly the same question that leads to the concept of hell or Hades, which is ingrained in the concept of hell. And then the next one is exactly the same question too, how will God set things right? That is the question that drives the entire biblical narrative. The flow of the Bible as a cohesive story sets up a problem in chapter 3, and that problem sets up the question of how will this problem be solved, and so that question is the core question of Jewish theology. And so that’s where you get connotations of there’s a return to Eden, a paradise, and the end of dying, the gift of eternal life, and then all of the different pieces of how theology conceived of what was wrong. For instance, Rome was in power and they weren’t supposed to be. The people of God who were tasked to be the people to rule the world in God’s stead on God’s behalf, Israel, was actually being beaten up by the powers of the world. All of the things in terms of how are things supposed to be, not just from a general philosophical level but from the Jewish scriptural story level, what was the thing supposed to be headed towards, that gets lumped in. Not because that’s the same question as what happens when I die, because it’s not. Just like we said with Hades. Hades is the answer to the question of what happens when I die. You go into the grave, some part of you kind of exists there. Gehenna is a very separate and different answer to the question of how will God set things right. He’ll hold people accountable. So some part of heaven is related to just what happens to us when we die; some part of heaven is related to God’s restoring peace and shalom on the world. Does that make sense? Connected but distinct?

Nate: Yes. So it’s the place we go, but it’s also… and I think that kind of gets merged together in some of this new creation, Jerusalem coming down. Isn’t that kind of merged together, it’s the place you go and it’s the setting to right?

Tim: Totally. So we’ll get into it in detail. Jerusalem is basically the best thing that ancient Israel ever had going, and therefore it becomes the symbol of the best. It becomes the new symbol for paradise. So at the beginning of the story, the symbol for paradise is a garden, and it’s a mountaintop garden that is a temple space where God and humans dwell. And we’re almost supposed to picture the gardens of Babylon and those beautiful hanging gardens that existed in the desert, it’s like this oasis thing. But once you have Jerusalem, that actually replaces as a fuller analogy, so the language of the new Jerusalem gets used as a sort of addition or second phase of the Eden analogy, which is basically the world capital of this perfect, beautiful city on a hill kind of deal. And so that phrase gets intertwined in this idea of a heaven or the new creation, the new heavens and the new earth, all of that. It’s why it’s been so hard. You’ve got this, like you said N.T. Wright trajectory that’s like, “No, it’s about our life here and now, it’s about God inaugurating His kingdom, that’s what the gospel story is about.” And then you’ve got these other people that are like, “No, it’s all about going to heaven.” But the concepts are intertwined. The concept of heaven is intertwined with the concept of new heavens and new earth. Even it’s there in the phrase, the new heavens and the new earth. So in that phrase for instance, that means new skies. New divine space and new human space. That’s what that means. But that phrase as a whole—new divine space, new human space—is heaven. It’s the newness of things, it’s the fixing of things, the restoration of things. So all of it’s intertwined. But there are parts of our caricature that it’s perfection. That’s kind of our caricature, it’s just nothing bad happens, only good things happen. If you watch any of the sitcom that came out this, was it this last year?

Nate: Yeah, I saw one or two episodes.

Tim: Yeah, it’s what it’s playing off of. So they’ll have little jokes of like, there’s endless froyo flavors or something. Because it’s this play off the caricature of it’s all just fun all the time. Kind of like a child’s imagination of heaven, if you let a kid pick what their heaven would be. But what we’ll see is there are other questions ingrained in what needs to be set right or how will God set things right? that are totally different from the questions that I think most of us modern readers bring to the text. So for instance we bring, how will I get all the froyo flavors I want? Maybe not that juvenile, but it’s like how will I just have bliss?

Nate: Bliss. Exactly. That idea.

Tim: Exactly.

Nate: The beach in Hawaii.

Tim: This perfect bliss. Right. I think one of the main question is actually, that the biblical authors had in their head, is how will human beings regain their rightful rule over earth? If they lived today they would say over planet earth; in the day they didn’t conceive of it as a planet. But that is, I think when they’re reading Genesis 1-11, that is the problem, is that divine beings have taken over humanity’s right to rule this space. How will human beings regain the right to rule this space, and how will they rule it well? And obviously incorporated into that question is, well who are the human beings that are supposed to rule it? Right? And at one level you have the people of Israel. At another level you have individual representatives of the people of Israel. But this whole concept of power, who is supposed to be in charge, it runs right through the heaven thing, and it’s actually the first one I want to get into because it’s to me kind of the most interesting and perhaps particularly pertinent. But this idea of rulership, so I think some parts of the church in the last ten to twenty years, with sort of a regained understanding of Jesus as inaugurated king of God’s kingdom and not just as this suffering sacrifice, some of this rulership stuff has been more focused on and I think better understood by protestant Christians. But I still don’t think we have any clue how central this idea was to any of the biblical writers, that the goal was… The best encapsulation of this is Paul’s little snide comment which is basically a slap on the wrist of “Don’t you know you will judge angels?” If that can be a snide comment that Paul makes, that he’s assuming yes, everyone knows that they will judge angels, that’s just a basic assumed part of early Christian theology, and we all read that and are like, “What the heck is Paul talking about?” That’s because it was part of the core concept. The story is that humanity’s supposed to be regaining its right to rule over the divine beings. Right now we are being ruled by the divine beings, and part of, and again it’s weird, part of how we’ll get there is we will sort of become like the divine beings in some way, somehow. Anyway, that question, how will humans regain the rule. And then the last one I’ll list is where you get into all sorts of hilarious logical hiccups, what is the nature of resurrection? So we won’t do it now, but you can trace the development of the idea and belief in resurrection long before New Testament. This was not a Christian invention. Throughout the Old Testament and then through other Jewish writings, but contingent in the idea of our bodies and lives coming back to life after we die brings us right back into those questions of are we mortal or immortal beings. At our essence what are we? You ask any person out on the street today and there will be total disagreement on are we… or just say Christians. Are human beings inherently immortal and death is unnatural, or are we inherently mortal and death is normal and to be expected? Philosophically. Obviously we know we all die, but philosophically that question of what does it mean to be human? And the kind of more practically: when we picture ourselves and our friends, so say imagine a hundred years from now, Nate, you and I are dead and we’re picturing ourselves being resurrected to life. What part of us will that be? What version of us will that be? How old will that version of us be?

Nate: Exactly.

Tim: And then will that world we are resurrected into be the same world? Will it be a different world? Will it somehow be kind of both those things at one time? All of those questions get lumped into concepts of heaven. I would say our conception of heaven is a simplification on one side of many of these questions. So for instance like we said, the escapism thing has come, escapism comes from saying heaven will only be different from this world. We can burn this world up and pollute it because it’s only different. You could go to the other spectrum and say heaven will only be exactly the same as this world, but there’s probably some blending of those two concepts going on in the biblical authors minds. And you could point to all of these questions and say not only is there blending of different answers to these questions, just like with the hell conversation, there’s diversity, so not all authors are going to think in exactly the same ways. The same authors won’t think consistently in every place. Not because they’re idiots, but just because they know these are complicated questions. So that’s just a list of them. You could add more to them. Hopefully it’s helpful to kind of zoom out and say that clearly all of those questions aren’t answered by one simple word, “heaven.” Right? That one simple word is a box that contains many different things, places, realms, concepts, ideas, hopes, and all of those things have been lumped into the box. So what I’m going to try to do is punch a hole in the side of the box, let everything out, and see all the different things that are in there.

Nate: That’s a very timely metaphor for us right now, but we’re both in the process of moving. You just moved and are moving in, and we’re about to move, so boxes. We’re in boxes. Okay, so are you confident enough to choose one of those questions for next episode and say this is where we’ll start at least, next episode? Which one?

Tim: Yeah, but [laughs] that doesn’t mean we’ll do it. Yeah, here’s a little teaser. I think the first one we’ll get into is heaven as a reversal of power. And so remember I said part of why I wanted to pin these conversations together is that I think it’s telling and informative if some of the concepts and questions surrounding heaven weren’t included with when we brainstormed what are the concepts and questions leading to our conception of hell. And when we got into it a little bit and I said part of the conception of hell for me at least, and I will argue that for the biblical authors as well is that of restraint of power, part of the key paradigm at work here is that Hitler can’t have power in hell. We can get into how that comes about, we could kill him, we could chain him up, we could torture him so he’s preoccupied, whatever. But part of the key idea is that Hitler can’t have power to do what Hitler wants to do with that power. And then you can get into the reality of most of us should not and cannot have the power to do some of the things we want to do with it. I make the same argument about heaven, that heaven is all about power, and so if a part of hell is the restraint from power, a core part of the basic idea of heaven is the giving of power to people who do not need to be restrained. Does that make sense?

Nate: Hmm. That’s cool.

Tim: So what we’ll get into is basically heaven, key part of the conception related to that power thing, we’ll see this, it’s so clear in some places, others it’s a little more murky, that sometimes heaven and hell is simply a way of saying the power structures that exist here and now will be reversed. So those who have power now will no longer have power; call that hell if you want. Those who have no power now will have power to rule; call that heaven if you want. So we’ll get into that, and we could have conversations forever that would be super fun. I actually love doing thought experiments related to power because it’s such a complex and all-encompassing thing. But since we have talked about power on the show and I’ve been forever trying to make the case that thinking around the concept of power and how significant social power is in the Bible, that that’s one of the central themes, I think it’d be a fun way to connect heaven and hell through that theme.

Nate: Yeah, that sounds fun, and it sounds in keeping with the main topic, the main theme of this whole show, which is the Bible is a story about power. Okay. So we’ll do that next time. Thanks so much for listening and for being on this journey with us. You’re not alone, and there are so many others journeying through this as well and trying to find their way, and we hope that the conversations we have here is helpful in that. And if you want more, we do have additional content that’s available on our Patreon page, including the Utterly Heretical podcast. Episode 1 is out now. You can find that all on almostheretical.com or just go straight to patreon.com/almostheretical. If you have any questions, thoughts, pushbacks, want to share your story, or anything like that. We’d love to hear it, we read every single email that comes in, and we’d love to hear from you. You can email us: contact@almostheretical.com. Alright, friends. We will catch you next time.

Tim: Peace, y’all.